Image by analogicus from Pixabay

You’ve done it! No more rat race. Let’s start planning your long-overdue trip to the Caribbean. The beach beckons…

But after you get back from the warm sands (and the ski slopes) you realize you have a good 35-40 years of this. You need to optimize your savings so that you’re getting the most out of it.

Part of that is how you invest that savings, but part is the sequence that you take your money out.

You have three buckets of money:

- Your taxable savings. This could be sitting in a brokerage account, or savings account.

- Depending on how this money is invested, it may generate either taxable income or taxable capital gains

- Your tax-deferred savings. This is your 401K and IRA money sitting in a traditional account.

- You got a tax break when you set this money aside. Unfortunately, when it comes out it will be taxed as income.

- Your tax-exempt, or “after-tax” savings. This is your Roth 401K account or Roth IRA.

- You already paid the taxes on this. This money and any earnings come out tax-free.

(Yes, you may have a fourth, fifth, and even sixth bucket: social security, pension, and/or an annuity. However, you are getting those regardless.)

The general guidance is to spend your savings in the order listed above—however, there are other considerations.

Your taxable savings is already being taxed. The thought is to spend this down first, while allowing your tax-advantaged accounts to continue to grow, unhindered by taxes.

Next, dive into your traditional IRAs and 401K. This money is going to be hit by Required Minimum Distributions (RMDs) at age 72*, so the smaller this account becomes, the better.

(*Yes, that age used to be 70½, but as of 2020 it’s now 72.)

This leaves your Roth 401K account and Roth IRAs for last. This is the most valuable money as it will never be taxed. If you can, let it grow.

But is following this order the best approach?

The reality is that you will most likely spend down all three buckets of money at the same time. The proportions, however, may vary based on your individual situation.

This is the point where your financial planner or CPA will need to help you out with the math.

One reason you might not want to spend down your taxable money first

When calculating what percentage of each bucket to take, one big consideration is whether you and your spouse plan to deplete it all or leave some for the kids and grandkids. Or charity.

Perhaps you are sitting on a big pile of stock in your brokerage account. Stock, that you purchased years, or even decades ago.

(I would argue that you aren’t being particularly diversified, but you may have your reasons.)

When you pass, your heirs will get a step-up in basis. This will save a huge amount in capital gains taxes.

- Perhaps you buy a stock at $5 a share. A decade later, it’s now worth $50 a share. If you were to cash out this stock, you’d owe tax on capital gains of $45 per share (50 minus 5).

- On your deathbed, the stock is now worth $80 a share. If you were to cash out now, you’d owe capital gains tax on $75.

- Upon your demise, your heirs will get the stock with a step-up in basis to $80. If they sell immediately there are zero capital gains, and therefore zero tax.

- They can always sit on the stock. Years later, the stock is worth $100 per share. If they were to sell at this point, they only pay taxes on capital gains of $20 a share (100 minus 80).

Remember that IRAs and 401K accounts can also be inherited, however, there is no step-up in basis.

The step-up rule is intended to simplify bookkeeping. You might not know how much Uncle Fred paid for those Apple shares you inherited.

Also, if Uncle Fred’s estate has to pay estate taxes (unlikely, as the 2020 limit is now $11,580,000), then those shares shouldn’t be taxed twice.

If you don’t need the money, another thing you can do with the appreciated stock is to gift it to charity. You’ll get a nice tax deduction, based on the fair market value of the stock.

But if that stock is earmarked for the family, then leave it alone.

Image ©Unknown via Canva.com

Keep your taxable money tax efficient

Ideally, sitting on a large chunk of stock isn’t recommended. Instead, invest the taxable money in your brokerage account in the most tax-efficient way possible.

And plan to spend it.

Some of this savings may be invested in a money market fund (“cash”) to cover emergencies and market downturns. Some may be invested in tax-free municipal bonds.

The rest may be invested in tax-efficient stock or stock funds. These tend to be growth funds of companies that grow, but don’t necessarily pay dividends. Dividends create income that is taxed.

If you prefer to invest in income-generating funds, such as bond funds and value stock funds, then keep those funds in your tax-advantaged accounts.

In your brokerage account, when you sell stock that has been held for over a year, you get the preferred long-term capital gains tax rate, instead of the higher tax rate for income. This also applies if the fund manager of your mutual fund or ETF also sells stock held for more than one year.

Regardless of what income level you are, the long-term capital gains tax rate will be less than the rate for income.

- For example, if your total income for the year is $80,000, your capital gains tax rate is 15%, while your top tax bracket for your income, such as salary or a traditional IRA withdrawal, is 22%

(Note, that in the tax world, “income” has two meanings. One meaning refers to the total amount of money you’ve acquired this year, eg. “gross income.” The second meaning refers to one type of money, which is taxed at a particular rate. Your salary, withdrawals from traditional IRAs, and money from bonds and non-qualified dividends are all taxed as income. Capital gains are separate from “income” but are included in total “income”.)

If you—or the fund manager—hold stock without selling, then no capital gains are generated even if the stock has appreciated in value.

For this reason, stock funds with “high turnover” are not as tax efficient as funds with low turnover.

To compare the tax efficiency of different funds simply compare the rate of return “before taxes” to the rate of return “after taxes on distribution”. Dividing the latter number by the former will give you a percentage, the tax efficiency. The higher the percentage, the better.

Drawing down the taxable brokerage account

In order to maintain your tax efficiency, some care will be needed when spending money from your taxable account.

If you have stock in your brokerage account that you’ve been sitting on awhile, cash it out during early low tax years and take advantage of little (or no) capital gains taxes

If your taxable account if full of individual stocks, you may wish to sell them and spend down the proceeds, before diving into the two tax-advantaged accounts.

Letting stock grow in value (or plummet—you never know) will cost you more in taxes in later years.

(Also, now that you’re retired, diversification is even more important. Ditch the individual stock positions.)

Spend down your money proportionally

Instead of spending down your three buckets of money in order, consider spending them down proportionally.

- Perhaps you have a million dollars saved: 300K in your taxable brokerage account, 600K in a traditional IRA, and 100K in a Roth.

- Determine how much of your savings you plan to spend in a given retirement year (including taxes). Then use 30% from the taxable account, 60% from the traditional IRA, and 10% from the Roth.

- For 50K of savings spent, that would be 15K from your taxable account, 30K from your traditional IRA, and 5K from the Roth.

Next year, do the same thing, adjusting the percentage as needed.

Fidelity has run a scenario comparing this approach of proportional spending, to spending the three buckets in order. In their analysis, the proportional spend plan paid significantly fewer taxes during retirement than the spending plan that first depleted the taxable account, then the traditional IRA/401K account, and finally the Roth.

Moreover, in their scenario, total savings lasted a year longer if savings was spent proportionally.

Why does this work? Even though the Roth may be small—as little as 10% in this example—every year it shaves off the highest tax bracket. Over a 30-40-year retirement, this tax savings adds up.

More taxes saved means more money that can grow. You’re more likely to make it to the end without running out.

Keep in mind, the Fidelity scenario is very simple. They assumed returns, as well as (inflation-adjusted) spending was constant throughout retirement.

The reality will be very different.

Image by Free-Photos from Pixabay

Different tax brackets during retirement

It makes sense to use proportionally more taxable money during those years when your income may be lower than average.

In this context, “taxable” refers to money that is taxed the most, such as your traditional IRA money and to some extent, your taxable brokerage money.

Starting out in a high tax bracket

Perhaps early in retirement, you plan to have fun and travel the world in style. While, in your later years, sit and crochet blankets in front of your “media device” of choice.

In this scenario, you are pulling out more money from your savings in your early years, and less in the later years.

Likewise, in your early retirement years, you may have no social security income. (You know that putting it off until age 70 works the best financially for most of us.)

In later years, with social security, you’ll need to pull less from your savings. Depending on your Modified Adjusted Gross Income (MAGI), either up to 50% or up to 85% of social security is taxable.

Stated another way, from 15% to 100% of your social security check is free of taxes!

Even if your lifestyle is consistent over time, you may be paying fewer taxes in your later retirement years due to social security.

(This assumes your Social Security plus RMDs are less than or equal to your annual living expenses at the time.)

Your traditional IRA/401K are the least tax-efficient—100% will be taxed as income—while your taxable account may be somewhat tax-efficient. Your Roth money, when withdrawn, will incur no taxes at all.

In years of heavier spending, you may wish to use more Roth, with a bit of taxable money from the brokerage account. Use the traditional IRA and 401K money only up to a certain threshold.

Starting out in a low tax bracket

The proportional size of your three buckets may also dictate your spending strategy.

Perhaps you start retirement sitting on a big pile of taxable money in your brokerage account.

Since you’ve invested this money in a tax-efficient manner, you can live off this money and not pay a lot of taxes.

Take advantage of these years in a low tax bracket to convert a chunk of traditional IRA or 401K money to Roth IRA money.

Obviously, a conversion will cost you in taxes, but that may be okay in a low tax year. You’re investing in your future by creating more Roth money.

If your proportion of Roth money is already large enough, alternatively, spend some traditional IRA money while you remain in a low tax bracket. This preserves more of your tax-efficient brokerage money.

Likewise, if you have a proportionally large traditional IRA or 401K account, use these early years to either spend or Roth convert a portion of it.

If your traditional account grows too large, once you hit age 72 and have both Social Security and RMDs, you may be pushed into a much higher tax bracket, especially if you are required to withdraw more in distributions than you need to live off.

Image by Kris Atomic on Unsplash

Medical and nursing home expenses near the end

The biggest reason your expenses may be higher near the end is due to medical and long-term care expenses. These expenses could be significant.

Fortunately, all “qualified medical expenses” are deductible on your taxes, above a certain threshold.

Yes, Medicare will pay for most of these expenses, but you may have to pay a big chunk on your own. For example, Medicare will pay for a stay at a hospital or an inpatient rehabilitation facility, but only for a limited time.

In addition, Medicare doesn’t cover custodial care. This is care that doesn’t need to be administered by a healthcare professional, such as help dressing, or bathing, or other activities of daily living. Or if you have dementia, someone to babysit you.

Unless you had the foresight to purchase long-term care insurance, you will be paying for these expenses on your own.

The good news? Long-term care, including custodial care, is considered a qualified medical expense and is, therefore, tax-deductible.

As such, you’ll want some taxable money left over to take advantage of the deduction. You don’t want to be living off your Roth (plus Social Security) exclusively because you’ve already depleted all your taxable money.

In this scenario, taxes you’ve paid in earlier years have effectively gone to waste.

If you don’t need long-term care quite yet, an assisted-living arrangement most likely won’t qualify for a tax deduction, unless it’s medically related.

In this situation, your expenses might be much higher than they were in your early retirement. You’ll need the Roth to keep you out of a higher tax bracket if your annual spending is higher than usual.

Obviously, none of us know where we may end up in the end. You may simply (and inexpensively) pass away in your sleep after a good day on the golf course.

Likewise, Congress will completely revamp the tax code several times during your retirement.

When you start your retirement, you may have no clue what your tax bracket will look like in the next several decades.

Therefore, it may be best to plan to have both Roth and taxable funds available at the very end.

Different tax bracket than your heirs

Another consideration, if you (and your spouse) plan to have money left over, is what type of bucket is best for your heirs.

Are your children retired themselves? Or are they still working like mad, most likely in their peak earning years, paying the highest tax rate?

If your heirs are in a higher tax bracket than you, they will benefit from the Roth account. If they are in a lower tax bracket, the traditional bucket will be better.

Unless your heirs decide to cash out their inherited IRA/401K (not recommended), they will most likely be required to empty the account within ten years, paying taxes along the way.

Fortunately, the Roth money will still come out tax-free for them. However, once out, any growth will be taxed as usual.

Be aware of tax bracket thresholds

So, each year you can spend down your three buckets of savings proportionally, with a few of the tweaks discussed above.

However, it’s useful to tweak those proportions if you are aware of the tax bracket thresholds.

The goal is to use your Roth to stay out of a higher tax bracket.

Tax calculations 101

Around December it may be useful to estimate your taxes for the year (or have your CPA do it). At this point, you may be able to make a few adjustments.

But more importantly, you can plan for the following year.

If it wasn’t for all the little rules and exceptions, calculating your taxes would be simple.

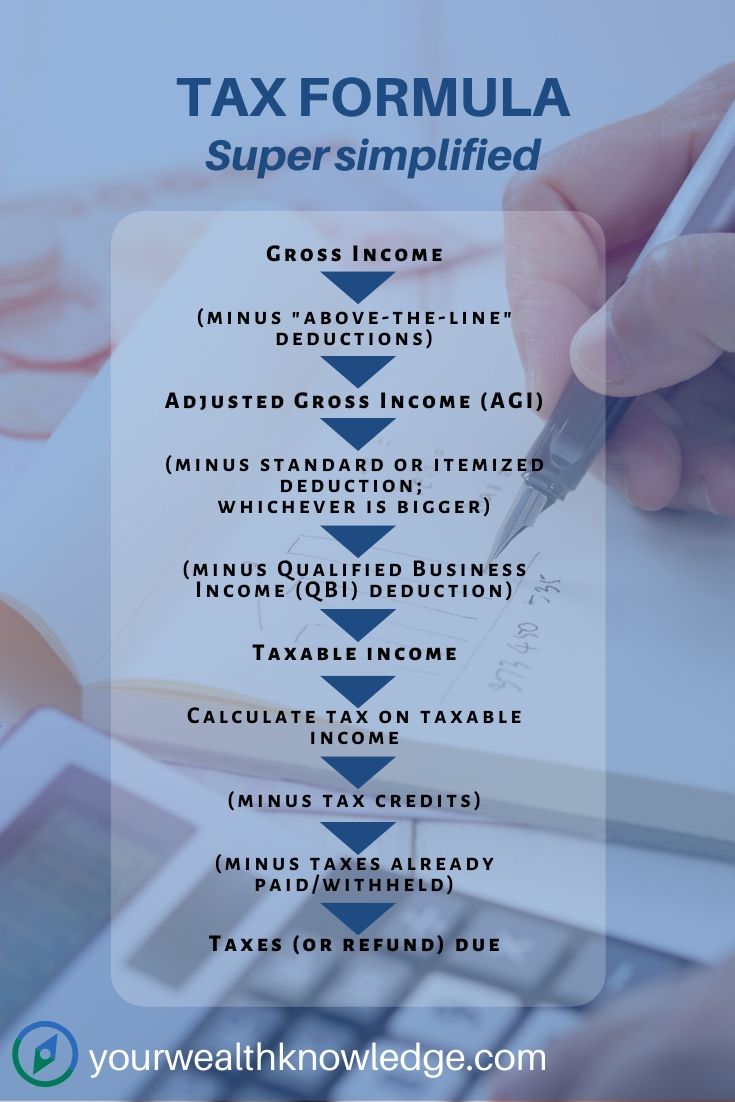

Shown is a super-oversimplified example of how taxes are calculated. Yours will probably be more complex.

Please seek out a financial professional for tax advice.

Start with Gross Income. This is all the money you obtained during the year, minus exclusions: your salary, Social Security, dividends, interest, capital gains, pensions, annuities, and distributions from your traditional IRA/401K.

“Exclusions” are sources of money that are not reported. This includes distributions from your Roth accounts.

Now come all the deductions. There are two types of deductions, “above-the-line” and “below-the-line”. In this context, the “line” is Adjusted Gross Income or AGI. Deductions are either applied before AGI or after AGI.

“Above-the-line” deductions are on Schedule 1. This includes the deduction for your IRA contribution, student loan interest, etc.

Most of your “below-the-line” deductions are on Schedule A. This includes state and local taxes (up to the 10K limit), medical and dental expenses (greater than 7.5% of your income), home mortgage interest, and charitable donations.

If you have no below-the-line deductions, no worries, simply subtract the standard deduction from your AGI. In 2020, the standard deduction is $12,400 for singles, and $24,800 for married filing jointly (MFJ).

If you “itemize” deductions on Schedule A and the total is greater than the standard deduction, then you can subtract that number instead.

The point of all this is that your standard (or itemized) deduction is like a zero tax bracket

You pay absolutely no taxes on the first $12,400 (or $24,800 for MFJ) you acquired this year.

Applying tax bracket thresholds

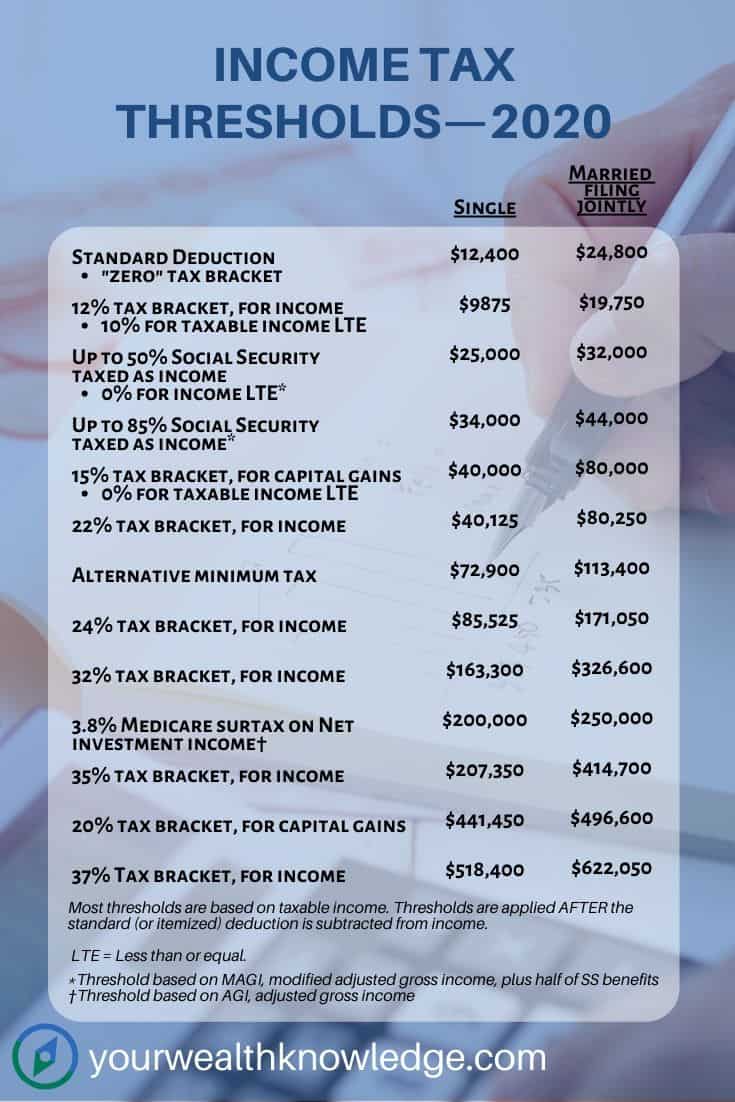

Numbers from IRS.gov

Any income above the standard deduction is first taxed at a 10% rate. Based on 2020 limits, at $9875 (or $19,750 if you’re MFJ) you hit the 12% bracket.

- Perhaps you’re single and your AGI is $40,000 this year

- The first $12,400 is the standard deduction and not taxed

- The next $9875 is taxed at 10% or $988 in taxes owed

- That leaves ($40K – $12.4K – $9875 =) $17,725 remaining that will be taxed at 12%, or $2127

- Total taxes owed: $2127 + $988 = $3115

(For simplicity sake, capital gains and social security have been ignored.)

Easy, right?

There are two spots where the current tax brackets make a big jump:

At $40,125 (or $80,250) you jump from 12% to 22%, a difference of 10%!

At $163,300 (or $326,600) you jump from 24% to 32%, a difference of 8%!

Let’s do another example.

- You’re a couple and your AGI is $150K

- The first $24,800 is not taxed, leaving $125,200

- Up to $80,250 will be taxed at 10% and 12%

- But the remaining $44,950 will be taxed at 22%!

Instead of paying that 22%, use your Roth to withdraw around $45K for the year. That would keep you nicely in the 12% bracket.

You can do this with any tax bracket threshold.

Withdraw from your Roth to stay out of the higher tax brackets.

These same thresholds are also useful for determining if you are currently in a “low” tax bracket. If you have some room before you hit a higher threshold, then consider the following:

- Do a Roth conversion,

- Cash out some of your traditional IRA/401K to spend next year

Note that a “low” tax bracket is relative. It will be different for each of us. In this case, “low” is relative to what your average year might look like.

Back to our example above. Perhaps a $150K AGI is “low” for you; your usual AGI is expected to be around $350K (above three more thresholds).

Either you were frugal this year, or you spent a big chunk of tax-efficient savings from your brokerage account.

In addition, you’re not fazed by a 22% or even a 24% tax bracket. You are, however, concerned with the 32% bracket. And you anticipate that you’ll have too much money in your traditional account (generating large RMDs when you turn 72).

- As before, you have $150K in living expenses paid from taxable accounts, leaving $125,200 after the standard deduction

- The 32% tax bracket is $326,600

- You plan to Roth convert around 200K ($326,600 – $125,200), bringing your AGI up to 325,200 right under the limit

Is your Roth bucket big enough?

All of these strategies work best with a proportionally sized Roth bucket.

Yes, even a Roth bucket as little as 10% of your total is useful in shaving off some of the highest taxes.

But as the example above showed, ideally, you’d like to stay below certain tax bracket thresholds.

- In one of the examples above, you used 45K of Roth money to stay out of the 22% tax bracket

- That 45K represented around a third of the 150K total you used that year

- Therefore, your Roth bucket should be about a third (or more) of your total savings

If you plan to maintain this lifestyle, and your Roth is on the small size, then consider Roth conversions during low tax years.

Note, these are very ROUGH estimates. There are a lot of variables at play: tax brackets WILL change, the rate of return on your three buckets won’t be consistent, and your lifestyle needs may change, sometimes unexpectedly.

Image ©Jodie Johnson via Canva.com

Building on the proportional strategy

Michael Kitces has modeled several strategies and has also found that splitting annual withdrawals between a traditional IRA/401K and a taxable brokerage account does consistently better than depleting one account before the other.

The two-bucket model, using the traditional IRA/401 to pay for half of expenses, maintained taxes below a critical tax threshold, while also preserving the tax-advantaged growth of the IRA/401K for future years.

What about the Roth bucket?

Consider the following model:

- Spend down the tax-efficient brokerage account first, and let the traditional IRA/401K grow

- Because your taxes are low in these early years, “fill-up” a tax bracket with Roth conversions

Over time your brokerage account goes away. Your traditional IRA/401K may stay about the same (depending on whether conversions have outpaced growth or vice versa). And your Roth will grow.

- Once the brokerage account is depleted, Roth conversions stop. Now the Roth is used to offset the tax burden of the traditional IRA/401K withdrawals.

Ideally, the same tax bracket can be preserved throughout retirement.

This model beats the two-bucket model above. As mentioned previously, the traditional IRA/401K is prevented from getting too large and incurring large, taxable RMDs.

If you don’t run out of money, your heirs may get a big Roth plus a smaller traditional account.

One last concern: health insurance

If your situation wasn’t complex enough, there is one more wrinkle to be aware of.

Once you quit your job, you’ll need to purchase health insurance on your own.

If you’re age 65, you’re eligible for Medicare.

Either way, there are huge savings on your premium if your income is below certain thresholds.

For the wealthy set, targeting the higher tax brackets, you’re ineligible.

However, if you’re targeting the lower tax brackets, you may wish to also stay below these other thresholds.

Good luck!

To summarize:

One strategy is to spend down your savings proportionally. Eg. If your Roth is 50% of your savings, then use your Roth to pay for 50% of your current annual living expenses.

Because you have no idea what your tax bracket will be at the very end, keep both taxable and tax-free Roth savings available.

Proportional spending may be tweaked:

- If your traditional IRA/401K is too large, and there’s a concern RMDs starting at age 72 will push you into a high tax bracket, then work on reducing this account

- Reduce your traditional IRA/401K by taking distributions in years when your tax bracket is low.

- Likewise, increase the size of your Roth, by converting a portion of traditional IRA/401K money

Be aware of tax bracket thresholds, especially those with a big percentage jump. Use your Roth, and tax-efficient growth from your brokerage fund, to keep your annual tax burden below key thresholds.

An alternative strategy is to spend down the tax-efficient brokerage account first. Take advantage of these low tax years to Roth convert portions of the traditional IRA/401K.

- As above, reduce the size of the traditional IRA/401K account to prevent potentially large RMDs later pushing you into a higher tax bracket

- Once the brokerage account is depleted, and traditional IRA/401K money needs to be withdrawn, use some of the Roth money to keep you in a lower tax bracket

This information has been provided for educational purposes only and should not be considered financial advice. Any opinions expressed are my own and may not be appropriate in all cases. All efforts have been made to provide accurate information; however, mistakes happen, and laws change; information may not be accurate at the time you read this. Links are included for reference but should not be considered an implied endorsement of these organizations or their products. Please seek out a licensed professional for current advice specific to your situation.

Liz Baker, PhD

I’m an authority on investing, retirement, and taxes. I love research and applying it to real-world problems. Together, let’s find our paths to financial freedom.