UPDATE: In December 2019, the SECURE Act became law

- Starting in 2020, the age when you must take Required Minimum Distributions (RMDs) from your Retirement account or IRA has been raised from 70½ to 72.

- Non-spouses that inherit an IRA or other Retirement Account in 2020 or later, can no longer take RMDs over their lifetime. Instead, the account must be emptied within ten years.

Tax rules and savings strategies for inherited traditional and Roth IRAs

At this point we all should be familiar with the rules for our own contributory IRAs. Unless an exception applies, we can’t touch our balance until age 59½, or else a ten percent penalty applies.

Once we exceed that age and start taking distributions, money from our traditional IRA is taxed as regular income. Money from our Roth, however, is not taxed at all. (As we paid the taxes when the money went in, way back when.)

One of the exceptions to the age 59½ requirement is death.

Every IRA (and every account your own) should have a beneficiary designation. It’s here where you list family members or friends which will receive your IRA in the case of your untimely death. (Whether you have a will or not, doesn’t matter in this case.)

Have you filled yours out?

Perhaps you’ve recently experienced a death in the family. You now may be the recipient of someone else’s IRA.

You may also be the beneficiary of a Qualified Retirement Plan, such as a 401K.

Most of the rules below are the same for both qualified plans and IRAs. (Note that some qualified plans have their own rules, which may limit your choices below.)

Cash it out?

Why yes, you can cash the entire thing out. No penalties apply.

Option 1: cash out some or all of it

But do you really want to?

If the IRA is of the traditional variety, you will owe taxes on the entire thing.

If the IRA is a Roth (and it’s been held for > 5 years) there will be no taxes.

Cashing out the Roth may be fine if you have a short-term financial goal, such as a down payment on a home, or college for your kids.

However, if you cash the Roth out now, and turn around and invest it in a regular taxable account, any earnings moving forward will be taxable.

Unless you can use the money today, its best to keep most of it intact.

Photo by Kristof Van Rentergem on Unsplash

Spouses

If you inherited the IRA from your dearly departed spouse, then you have the most flexibility.

Option 2: simply roll it into your own traditional or Roth IRA, and leave it be (spouses only)

If allowed, you can even roll it into your qualified retirement plan, such as a 401K or 403(b).

Obviously, once you do this the money is trapped, with the usual IRA or 401K distribution rules. If you change your mind and want the cash, it’s too late.

In addition to putting the money in your own tax-deferred accounts, you also have other options.

Spouses and other “eligible designated beneficiaries”

You may be a son, daughter, sibling, grandchild, or friend to the deceased. Your options are a little more limiting.

You must keep the inherited IRA separate from your own IRAs. It will stay in the name of the deceased, even though you have control of it. You also can’t roll it back into a 401K.

You also can’t sit on it indefinitely.

Option 3: take Required Minimum Distributions (RMDs) over your lifetime

If you were not a spouse and inherited before December 31st, 2019, this was the best option for you.

However, the rules have changed. Starting in 2020, you can only take this option if one of the following exceptions applies:

- You’re the spouse

- You’re disabled or chronically ill

- You’re not more than ten years younger than the decedent. (In other words, you’re close in age or older.)

- You’re a minor child of the decedent. (But once you reach the age of majority, the ten-year rule applies)

The IRS wants their taxes! Based on how long the IRS thinks you are going to live, a certain portion of your IRA needs to be distributed every year. In other words, removed and taxed.

You can either spend your RMD on your usual living expenses or reinvest it in a taxable account. You may also have the option of transferring invested shares from one account to the other so that your money can continue to grow—now subject to the usual taxes.

Mathematically, if you live as long as the IRS believes, the entire thing will be distributed by the end of your life.

With your own IRA, you need to take RMDs when you hit age 72 (recently changed from age 70½). (Likewise, the spouse that rolled an inherited IRA into their own.)

But if you choose option 3, then you need to start taking RMDs as soon as you take possession of the IRA. This also applies if you’re the spouse and chose this option.

Indeed, you may need to pay the last RMD of the deceased.

Presumably, you are younger than the deceased, and therefore your RMDs will be less than theirs (assuming they were old enough to start taking RMDs themselves).

If you happen to be older than the deceased, you have the option of taking RMDs over their longer life expectancy.

Image by Pete Linforth from Pixabay

Deceased wasn’t taking RMDs

The deceased may have died “early” before reaching age 72 (formerly age 70½) when they would have been required to take RMDs. Also, if they had a Roth IRA, no RMDs would be required of them at all.

As a spouse, additional options are available.

Option 3b: Instead of taking RMDs immediately, spouses have the option of starting RMDs when the deceased would’ve turned 72

As a spouse, if you’re younger, and therefore hit age 72 later, it may be better to roll the inherited IRA over to your own IRA—assuming you know you won’t need the cash.

Non-spouses and the new ten-year rule

As of January 2020, the new SECURE Act goes into effect. IRAs inherited before December 31st, 2019 follow the old rules.

However, moving forward, non-spouses that don’t otherwise meet one of the exceptions listed above (disabled, chronically ill, a minor, etc.) must empty their inherited tax-advantaged account sometime before the end of the tenth year following the year they inherited.

Option 4: Remove your inherited funds with ten years

The good news is that there are no rules about how you do this. You can take 10% every year or wait until the final year.

The smart thing to do, however, is waiting until you have a year or two with low taxes.

- For example, perhaps you’re planning to retire (or take a “break” from work) within the next ten years. Wait until then to move your money.

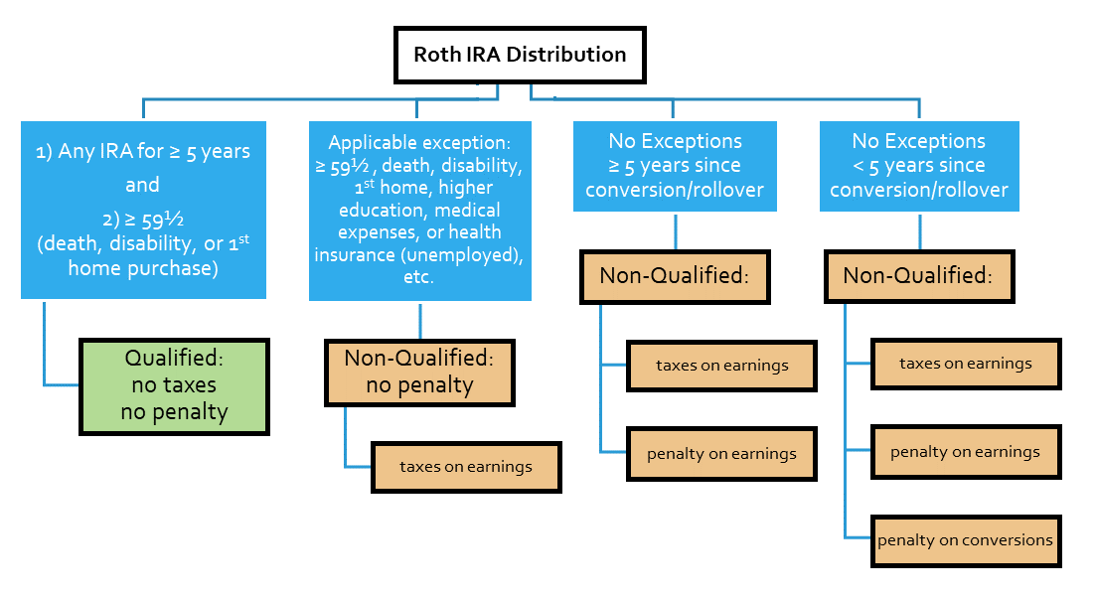

Five-year rules (for Roth IRAs)

There are two five-year rules that apply to all Roth IRAs (regular and inherited):

- If you take a Roth IRA distribution, it must occur at least five years after the very first Roth IRA you started. (Oddly, any time in a Roth 401K account only counts for that account. If you roll it over, unless you already have a Roth IRA, the five-year timer starts over.)

- If you take a Roth IRA distribution from funds converted from a traditional IRA, this distribution must occur at least five years after that conversion

If you fail either of the five-year rules, your earnings may be subject to taxes and possible penalties. If you are over 59½, disabled, or dead, the second rule no longer applies.

If you are age 59½ or older, (dead, disabled, or using your distribution for a first-time home purchase), AND you’ve had a Roth IRA for at least 5 years, then the distribution is a “Qualified Distribution” and no penalties or taxes apply. If your distribution is not qualified, then taxes or penalties may apply, depending on the situation. Penalties = 10% additional tax

Fortunately, it’s relatively easy to avoid these pitfalls as Roth money comes out in a particular order:

- Original contributions

- Conversions

- Earnings

Original contributions can come out any time, penalty and tax-free. Conversions can come out once their five-year rule has been met.

Earnings, on the other hand, may get hit with taxes and/or penalties, unless the required criteria are met.

Assuming, you didn’t gut your Roth when taking money out, you’re probably in the clear.

(Not that you should be taking money out of your Roth. . . But if its an emergency. . .)

Inherited Roth IRAs

When it comes to inherited Roth IRAs, you also “inherit” the years applicable to the five-year rules.

The second rule regarding conversion no longer applies after death, but the first rule still applies.

If the deceased set up their very first Roth, perhaps as a conversion, a year before their death, it will take an additional four years until the five-year rule is met.

Yes, if you meet one of the criteria above, you may be taking RMDs, but hopefully, those RMDs are coming from the contribution or conversion layer. You also have option 4 above, which gives you five years to wait.

Rollovers

If you inherit a 401K, you may leave it there, or roll it over to an inherited IRA. If you’re the spouse, you have the additional option of rolling it into your own IRA or 401K plan (if allowed).

Likewise, you can rollover an inherited IRA from one financial institution to another (“trustee to trustee”), just as you can with your own IRA.

Converting a traditional inherited IRA to a Roth?

Sorry, no, you can’t convert your inherited IRA.

Nor can you make annual contributions to it. Those go into your own IRA, held in a separate account.

Obviously, the spouse who has chosen to place the inherited IRA money in their own IRA is an exception. Once it’s your own IRA, you can treat it like any regular IRA and convert whenever you like. (Don’t forget the taxes owed.)

There is another exception if you happen to inherit a qualified plan, rather than an IRA. Regardless of whether you are a spouse or not, and the plan allows it, you can rollover your traditional funds to an Inherited Roth IRA and pay the usual taxes.

However, doing this type of conversion isn’t necessarily recommended. As a non-spouse, you are required to take RMDs regardless of whether it’s a traditional or Roth inherited IRA, which will gradually deplete this account over time.

It’s far better to “spend” your taxes converting one of your own traditional IRAs or an old 401K. Recall that you are never required to take RMDs on your own Roth IRA.

Photo by sergio souza from Pexels

Disclaiming your inheritance

Perhaps you don’t need the money (and certainly not the taxes) and there are other beneficiaries that could use the money more.

You always have the option of “disclaiming” part or all of an inheritance, such as an inherited IRA.

Once you disclaim, the money goes to the other beneficiaries. (If there are no beneficiaries it goes back to the estate.) Make sure you’re sure, as you can’t take it back. Fortunately, you have up to nine months to decide.

Perhaps you’re the spouse, but you don’t need the money and your RMDs would be rather hefty at your “advanced age”. Instead, disclaim the IRA and let the secondary beneficiaries inherit.

These beneficiaries maybe your children or even grandchildren.

If a beneficiary is a minor child of the deceased, they can take (small) RMDs until they reach the age of majority. At that point, the ten-year rule will kick in.

Other beneficiaries will have to follow the ten-year rule. This is fine, assuming they are in a lower tax bracket than you. (Or are planning to be in a lower tax bracket within the next ten years.)

Disclaiming is much more efficient than having your loved ones wait until you die to inherit. At that point, your IRA will be somewhat depleted due to all the RMDs you had to take.

Also, you can see your loved ones enjoy their inheritance today when it could be key to securing their own financial futures.

Depending on your cash needs, you have several options for cashing out or letting (most) of your inherited IRA grow free of taxes until you need it.

- Cash out part or all of it

- (Spouses only.) Roll it into your own traditional or Roth IRA.

- Take Required Minimum Distributions (RMDs) over your lifetime (spouses and eligible beneficiaries only)

- (Spouses only.) Start RMDs when the deceased would’ve turned 72.

- Empty the account within ten years

- Disclaim part or all of it

Additional Reading

- Self-employed? Open Your Own 401K Account. Tax-advantaged retirement savings options are not just for Big Companies

- How Long Will You Live? (According to the Government). Or more importantly, how long does your savings need to last?

- Roth vs Traditional. Picking where to stash your retirement money for the best tax-advantaged growth

This information has been provided for educational purposes only and should not be considered financial advice. Any opinions expressed are my own and may not be appropriate in all cases. All efforts have been made to provide accurate information; however, mistakes happen, and laws change; information may not be accurate at the time you read this. Links are included for reference but should not be considered an implied endorsement of these organizations or their products. Please seek out a licensed professional for current advice specific to your situation.

Liz Baker, PhD

I’m an authority on investing, retirement, and taxes. I love research and applying it to real-world problems. Together, let’s find our paths to financial freedom.