All of us hear a lot in the press about how Social Security is quickly running out of money. This begs the question, will there be any left decades from now when it’s our turn?

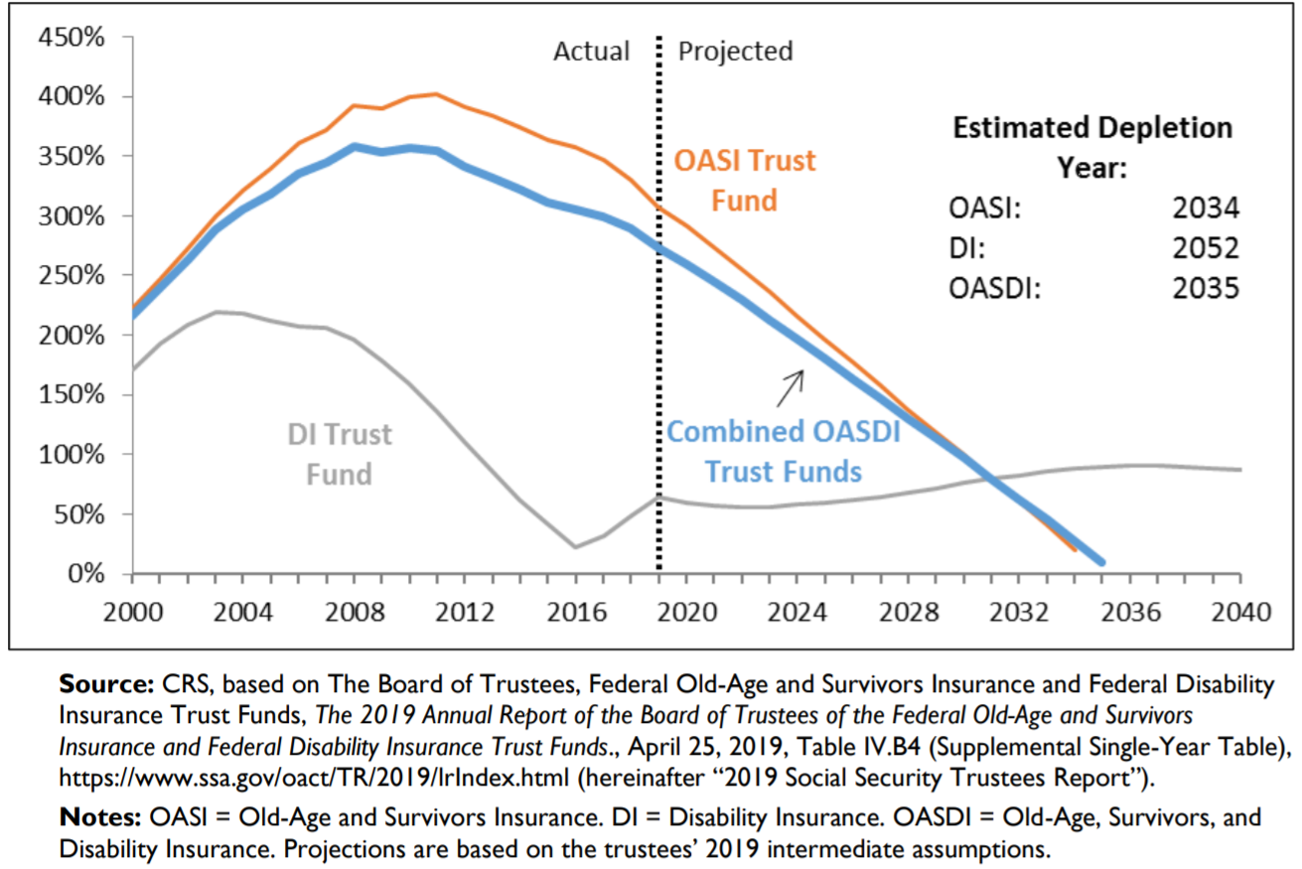

According to the official 2019 OASDI Trustees Report, trust fund reserves will become depleted in 2035

Actual and Projected Trust Fund Ratios, by Trust Fund, 2000-2040

(trust funds assets at the beginning of the year as a share of annual expenditures)

Reprinted from the Congressional Research Service report: “Social Security: What Would Happen If the Trust Funds Ran Out?”, Updated June 12, 2019. (Any CRS Report may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without permission from CRS.)

This is not as bad as it sounds. The reserves may be gone but workers will still be paying social security taxes into the system. Those taxes will then be used to pay out social security.

According to the Trustees report, unless Congress acts, in 2035 social security payouts will be reduced to 80% of their current amount and continue to be reduced to as low as 75% by 2093, the last year of their projection

That’s the worst-case scenario. Most likely, Congress will act and do something about it.

The Social Security system

Old-Age, Survivors, and Disability Insurance (OASDI) is covered by two trust funds, one for Old-Age Survivors Insurance (OASI) and a second trust fund for Disability Insurance (DI). Together, the two trusts are referred to as OASDI.

OASI will run out in 2034 and DI will run out in 2052, but together they will run out in 2035.

If you are employed, then up to 6.2% of your paycheck goes to the government to pay into these two trusts. Your employer pays another 6.2%. If you are self-employed you pay all of it or 12.4%.

(In addition, you and your employer each pay another 1.45% for Medicare, for a total of 15.3% for every worker.)

The good news: social security is only taxed up to a certain wage, which is $132,900 in 2019. So, any money you earn above this amount is not subject to social security taxes (but is still taxed for Medicare).

Retirement benefits

You may claim your retirement benefits any time after turning age 62. You can even continue to work; however, your benefits may be reduced.

It is preferred that you wait until your official retirement age: 67 for all of us born after 1960. It is at this age that you will receive your “full retirement benefit”. Any earlier, and your benefit is incrementally reduced, with a maximum 30% reduction at age 62.

If you wish to start benefits at say, age 65, your benefit will be reduced 5/9 of one percent for each month before your full retirement date, up to 36 months. For greater than 36 months, your benefit is further reduced by 5/12 of one percent each month, which equals 5% per year.

- For example, at age 65 you may be retiring 24 months early, and have your benefits reduced by 13.33% (24 x 5/9)

[flip your phone sideways for easier viewing]

Adjustments to retirement benefits based on age. For those born after 1960 with a full retirement age of 67.

You can also choose to delay receiving benefits and get a bonus. For those of us born after 1943, the bonus is 8% per year of delay up to age 70. If your full retirement age is 67, that represents three years or a 24% increase.

Keep in mind that Social Security benefits were never intended as a replacement for your pre-retirement income. Also, the more you make now, the smaller this replacement percentage is. You may be getting more than your lower-income acquaintances, but it will be a smaller percentage of what you need.

In 2019 the replacement percentages are estimated at 55% for low earners, 41% for medium earners, and 34% for higher earners.

A pyramid scheme

Social Security is the ultimate pyramid scheme. We pay into it, which is used to pay current social security benefits. Then when it’s our turn, the younger generation will work to pay for our social security. The problem is, we are all living longer and pulling out more benefits than we put in during our working lives.

When the program started in 1945 there were almost 42 covered workers per OASDI beneficiary. At present, there are only 2.8 workers per beneficiary.

The trusts earn interest on their investments, but it isn’t enough. Last year, the government took in roughly 1 trillion in total income for OASDI, mostly from payroll tax contributions. Only $83 billion came from interest or roughly 8% of their total income.

As you would expect, the trusts invest exclusively in US treasuries. Given our low-interest-rate environment for the last few decades, it’s no surprise that interest income is low.

A useful ratio to follow is the trust fund ratio. This is the balance at the beginning of the year, divided by anticipated spending for that year. This ratio peaked in 2008 at 358% and is now currently 289% and dropping. In other words, without incoming payroll taxes, the trusts could cover less than three years of benefits.

Once the ratio reaches zero, the trusts are insolvent.

Insolvency?

The Congressional Research Service (CRS), prepared a report for Congress: “Social Security: What Would Happen If the Trust Funds Ran Out?”. It’s an excellent read.

The report reminds us that “insolvency” will simply occur when annual expenditures from the trusts, such as Social Security payments, are greater than income. The system isn’t “completely broke.”

Then what happens?

There are a few laws in place that complicate things (which obviously Congress could change). The Social Security Act requires that benefit payments come ONLY from the trust funds. And the Antideficiency Act prohibits the government from spending more than they have.

In the case of insolvency, these two laws would restrict the full payment of social security benefits in a timely manner.

However, the Social Security Act, also requires that everyone that is entitled to benefits should get their full benefits. Just because the trusts are insolvent is no excuse.

If not fixed, this could lead to an interesting legal situation, where beneficiaries could, in theory, take legal action. Who knows how that could play out…

Per the CRS report, either social security benefit checks for the full amount will be paid late, or checks will be paid on time, but for a reduced amount.

Most likely the situation will not get to this point. Congress will do something.

Photo by Engin Akyurt from Pexels

This is not the first time

I was surprised to learn that this isn’t the first time that the OASDI has faced insolvency.

In 1982 the Trustee report predicted the OASI would become insolvent by the following year! Congress stepped in and allowed the OASI trust to temporarily borrow from other trusts.

In the meantime, Congress enacted the Social Security Amendment of 1983 to increase social security income and reduce spending. This amendment included many significant changes, including:

- Cost-of-living-adjustments (COLA) were to be delayed by six months moving forward, and calculated using a different methodology

- Up to 50% of benefits of higher-income beneficiaries were now subject to income tax

Today, up to 85% of benefits are taxable for high-income retirees, thanks to a law enacted in 1993. But before 1983 social security benefits were never taxed.

- The tax rate for self-employed was increased

In 1983 it was 8.05%. With the new law, it jumped to 11.4% in 1984 and increased to our current rate of 12.4% by 1990. On the plus side, the amendment added a tax deduction.

- Scheduled increases in payroll taxes for both employees and employers were to occur sooner

In 1983, payroll taxes were only 5.4% for OASDI. The next increase to 5.7% was originally scheduled for 1985 but was moved up to 1984. This rate continued to increase until 1990 when it hit the 6.2% rate we have today.

- The definition of full retirement age was adjusted upward

Before 1983 full retirement was age 65. With the amendment, those born in 1937 or older (age 46 in 1983) could still retire at age 65 with full benefits. However, everyone younger had months to years added to their full retirement age. Because of this amendment, the full retirement age for everyone born in 1960 or later is currently age 67.

- Benefits were reduced for those retiring early at age 62.

Before 1983 your benefits could be reduced by as much as 20% if you retired early at age 62. (Less if you retired between age 62 and your full retirement age of 65.) The new amendment increased that to the maximum 30% reduction we have today.

Thanks to these and many other changes, the OASI loan was paid off in 1986 and solvency was assured for the time being. Crisis averted.

Nor the second time

In 2015 the trustees again predicted insolvency, this time with the DI fund. This was predicted to occur by late 2016.

Late in 2015, the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2015 (BBA 2015) was passed and allowed a temporary re-allocation of more payroll tax towards the DI fund and less towards the OASI fund. By this year, 2019, the allocation between the two funds should return to normal, pre-2015 levels.

What can Congress do?

The Social Security Amendment of 1983 is an example of how this problem can be managed by Congress with a multi-pronged approach.

The CRS report focuses on what Congress can do after they fail to act in a timely fashion and the trusts become insolvent. (Do I detect a bit of cynicism in this official document?)

Two policy options are presented:

- The Benefit cut scenario, where benefits are cut across the board

- The Tax increase scenario, where payroll tax rates would increase

Based on the numbers from the 2019 Trustees report, 20% across the board cut would be required initially. This cut would need to increase to 25% by 2093.

This would reduce the income replacement percentages from 55%, 41%, and 34% for low-, medium-, and high earners, to only 42%, 31%, and 26%.

- If you are a high earner, then only 26% of your pre-retirement income would come from Social Security. You’ll need to make up the difference yourself.

There are variations on this scenario. Perhaps maintain benefits for low earners but decrease the benefits for everyone else to make up for it.

In the second scenario, payroll tax rates would need to increase. Based on the numbers from the Trustees report, an increase of 3.2% would be required.

That’s a change from 12.4% to 15.6%. The rate would need to continue to increase to 16.5% by 2093.

Another thing they can do is raise the income limit of $132,900 so those earning more would pay additional payroll tax.

Hopefully, Congress will act before this point. The final solution will most likely be a multi-pronged approach. Payroll taxes will most likely go up. Benefits may be cut, but more likely “full retirement age” will again be increased. The percentage of benefits lost by retiring early could also be increased.

The changes may be across the board, in the case of payroll taxes, or they may be limited to those furthest from retirement. (Sorry millennials.)

In the meantime, anecdotally, many financial planners are recommending including only 75% of your projected social security benefits in your retirement planning estimates.

Good luck!

Check out the Social Security Quick Reference Guide:

Additional Reading

- Need More Money to Retire? Consider a Reverse Mortgage. One option to generate a guaranteed income stream for your remaining years

How Much Money Do You Need to Retire Comfortably? How big is the stash, and how much do you need to save to get there?

Will You Run Out of Money? Closing in on retirement? How to manage your existing savings to last

This information has been provided for educational purposes only and should not be considered financial advice. Any opinions expressed are my own and may not be appropriate in all cases. All efforts have been made to provide accurate information; however, mistakes happen, and laws change; information may not be accurate at the time you read this. Links are included for reference but should not be considered an implied endorsement of these organizations or their products. Please seek out a licensed professional for current advice specific to your situation.

Liz Baker, PhD

I’m an authority on investing, retirement, and taxes. I love research and applying it to real-world problems. Together, let’s find our paths to financial freedom.