2023 UPDATE

Contribution Limits for 2023

From IRS.gov

- IRA contribution of $6,500, with $1,000 catch-up

- 401K contribution of $22,500 with $7,500 catch-up

- SIMPLE contribution of $15,500 with $3,500 catch-up

TOTAL contribution for a defined contribution plan (like a 401K) of $66,000

- TOTAL includes contributions from employee, employer, and after-tax

- With catch-up contributions, the TOTAL becomes $73,5000

For more information see our TAX SAVINGS page

Image by Theodor Moise from Pixabay

Congratulations. Your career is going well and FINALLY, you are making some real money.

But up to this point perhaps you’ve been a bit lax when it comes to saving for your retirement. There were those student loan debts, then a home purchase with a hefty mortgage. And all your kids needed braces.

You’re playing catch-up. You’ve managed to contribute the maximum allowed to your 401K, which is $19,500 in 2020.

But you’ve run the math and that won’t be enough.

You can save more, but taxes will eat into your return. If you’re making REAL money, then you’re subject to REAL taxes in the higher tax brackets.

Where can you stash these extra savings and still enjoy tax-advantaged growth?

1. Turning 50 this year? Up your contribution

You should already know this, but it bears repeating. If you turn 50 this year you can add catch-up contributions to your 401K, in the amount of $6500, for a total contribution of $26,000.

Likewise, if you have a SIMPLE plan instead of a 401K, you can add an additional $3,000, for a total contribution of $16,500.

For IRAs, you may contribute an extra $1000, for a total $7000 contribution.

2. Non-deductible IRA contribution

If you make real money, then you can’t contribute to a Roth IRA this year. Single, you’re out with an adjusted gross income (AGI) of $139,000 or greater; married filing jointly (MFJ) and you’re out with an AGI of $206,000 or greater.

Ok, no Roth.

Regardless of income, you can always make a traditional IRA contribution.

However, if you (or your spouse) have a 401K or other qualified plan, at work there is another set of income limits that dictate whether the IRA contribution is tax-deductible. Singles are out at ≥ $75,000 AGI; MFJ are out at ≥ $124,000 if both of you have a plan at work.

So, if you can’t get a tax deduction should you still contribute to a traditional IRA this year?

Absolutely.

Yes, you’ll get taxed on both the front end and the back end. But all that lovely savings gets to grow tax-free until you take it out decades from now.

You could stop there, but there is another neat trick: the backdoor Roth conversion

The Backdoor Roth Conversion

At any time, you can convert any amount of traditional IRA money to Roth money. You simply need to pay the taxes, so timing and strategy are critical.

You can do the same with “after-tax” IRA contributions.

You’ve already paid the taxes, so no taxes are owed right?

Well maybe…

Image by Pixabay

Beware the pro-rata rule

As far as the IRS is concerned, all your traditional IRA money exists in one big figurative account. It doesn’t matter if you keep your IRA money in several different accounts. SEP-IRAs and SIMPLE-IRAs are also included.

(Obviously, ignore your Roth IRA money.)

Perhaps you have $100K in all your IRAs, which includes that $6000 after-tax contribution you just made.

You do a Roth conversion of $6000.

Pro-rata means that a proportion of that $6000 came from the after-tax IRA money and the rest came from the regular pre-tax IRA money. So, you’ll owe taxes on $5640 ((100-6)/100 x 6000).

The easiest way to avoid the pro-rata rule is to not have a big traditional IRA.

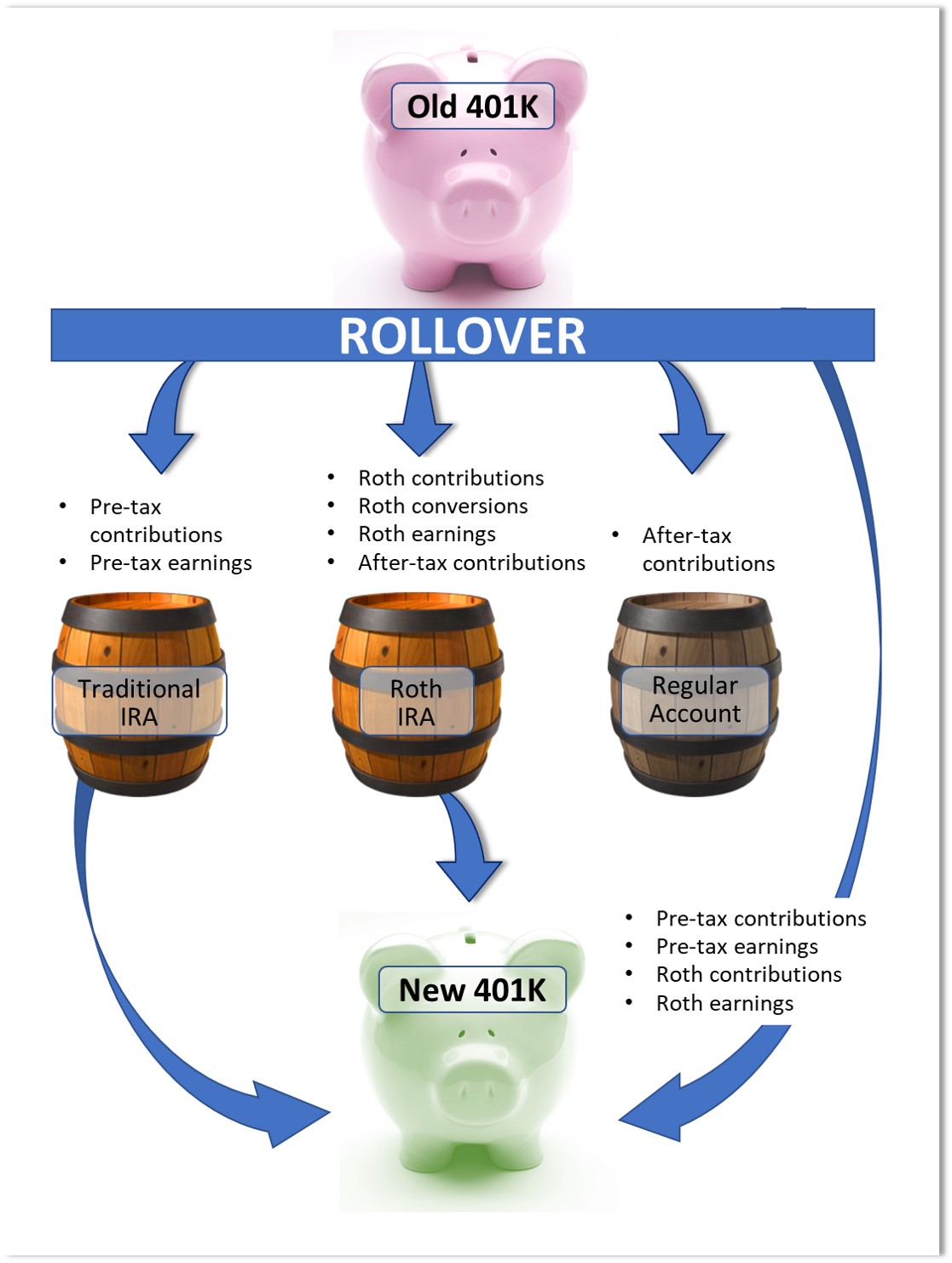

In a previous post, I discussed at length rollover strategies for your 401K and IRAs.

Your Roth IRA is fine, but any traditional IRA money that you don’t plan to Roth convert should be rolled back into your current 401K. (Assuming your 401K allows it and you don’t plan on any in-plan Roth conversions—see below.)

In the scenario above, you roll $70,000 back into your 401K. That now leaves you $30K in your traditional IRA that you plan to Roth convert over the next few years.

You do a Roth conversion of $6000.

Now you’ll owe taxes on $4800 ((30-6)/30 x 6000).

If you had rolled over your entire IRA and left only the $6000 you would owe no taxes. (Or perhaps just a bit on any earnings made in the interim.)

3. After-tax 401K contributions

An extra $6000 (or $7000) in your IRA stash is well and good, but you need to save a lot more.

No worries. We’re getting to the big money…

If your 401K plan allows it, you can go over the $19,500/$26,000 contribution limit.

These excess contributions will not be tax-deductible and are referred to as after-tax contributions.

Don’t confuse these with Roth account contributions to your 401K which are technically “after-tax” as well. All Roth contributions must be within your $19.5K contribution limit.

Your total contribution limit for 2020 is $57,000 (or $63,500 for the 50-and-over set). This limit covers everything, including contributions your employer makes to your 401K account.

Odds are your employer is only moderately generous and you’ll have plenty left in the limit to make after-tax contributions.

The Mega-Backdoor Roth Conversion

Like in the IRA situation, you can also Roth convert these after-tax contributions.

In-plan Roth rollovers allowed

If you’re lucky, your employer supports in-plan Roth rollovers. Simply initiate a rollover of these after-tax dollars.

Taxes may or may not apply.

Keep in mind that 401Ks also follow the pro-rata rule, so if you have a big chunk of traditional money you’ll be paying taxes.

Did this big chunk of traditional money come from an IRA rollover or a direct rollover from your old 401K plan?

If you’re planning to convert all of it eventually, it doesn’t particularly matter where its located, as you’ll be paying taxes eventually.

But if you plan to contribute a lot of after-tax money to your current 401K, followed by an in-plan Roth conversion, then it’s best not to have a lot of traditional money sitting in the account.

If you’ve already contributed or rolled traditional money in from somewhere else, it’s too late.

But with a bit of foresight you can decide what to do with this chunk of traditional money:

- Leave it in an old 401K, from a previous job

- Roll it into a traditional IRA

- Roll it into your current 401K

There are pros and cons to each.

- You can keep traditional money in an old 401K. But if there are significant after-tax funds sitting there, you can’t Roth convert any of that money until the entire 401K is rolled over. After-tax money always comes out last in a direct rollover.

- You could rollover all your old 401K funds into two IRAs. After-tax contributions and Roth money will go into a Roth IRA. Earnings from that after-tax money and your traditional money will go into a traditional IRA. However, now you have pro-rata issues if you choose to Roth convert nondeductible IRA contributions (above).

- However, a $6000/7000 IRA contribution is probably a lot less than what you can contribute to your 401K after-tax. It’s a trade-off.

- In short, if you don’t plan to eventually Roth convert traditional money, then sequester it in the account with the least amount of current or anticipated after-tax funds. Either an old 401K, an IRA, or your new 401K.

- (Although multiple IRAs must follow the aggregation rule and be counted as one big IRA, the same does not apply to 401K accounts. They are treated as separate accounts.)

When you leave your old job, if you like you may rollover your old 401K either to an appropriate IRA or the 401K of your next job. After-tax contributions can go into your regular checking account, but they’re better going to a Roth IRA.

In-plan Roth rollovers not allowed

Your new 401K may not support in-plan Roth rollovers. (But let’s hope it at least supports a Roth account to receive Roth contributions.)

In this scenario, you can still make after-tax contributions, but you’ll have to wait until you leave this job to do anything about them.

The unfortunate thing is that the earnings on these contributions are treated as traditional money.

You’ll recall that earnings on Roth money are also considered Roth money. Assuming you follow all the rules, earned Roth money is never ever taxed.

Once you leave your job you can rollover these after-tax dollars into your Roth IRA.

(Sorry, but you can’t roll them into the 401K of your next job. That 401K may take either traditional or Roth money, but it won’t take the after-tax money.)

You also have the option of simply taking the after-tax money and putting it into your checking account, penalty- and tax-free.

But that would completely defeat the purpose of the Mega-Backdoor Roth Conversion.

Again, earnings on those after-tax dollars will be treated as traditional money. As such you can either roll that money into a traditional IRA or your next 401K.

If you like, you can Roth convert it and move it to your Roth IRA instead.

Note that if you can’t do in-plan Roth conversions it doesn’t matter how much traditional money you have in this 401K. You can hold it there while you conduct Backdoor Roth conversions between your IRA accounts.

4. Annuity purchase

If you’ve contributed as much as you can to both your 401K and IRA and still have money to save, consider either an annuity or life insurance.

Both financial vehicles allow your money to grow tax-free.

In addition, both are important in your overall retirement planning strategy. To summarize, the guaranteed payment of an annuity can supplement Social Security and pay you for life. You don’t have to worry about living too long and running out of money.

Likewise, life insurance will guarantee that you’ll leave a legacy to your loved ones. You can freely spend all your savings during your lifetime, and not worry about setting aside a significant chunk.

Deferred annuity

You can purchase a deferred annuity that won’t start paying out until a time that you specify, sometime after retirement.

(In contrast, an annuity that starts within one year of purchase is called an immediate annuity.)

For example, you could purchase an annuity at age 55, with the intention of not starting it (“annuitizing” it) until age 65.

For deferred annuities, you have a choice between making a single large payment (“single premium”) or many payments over a certain timeframe (“flexible premium”)

You may have the option of purchasing an annuity within your employer retirement plan. These are called qualified annuities and are considered redundant as your employer plan already has tax advantages. In our scenario, you’ve already maxed out your employer account, so this type of annuity won’t help.

Image by Thomas Staub from Pixabay

A non-qualified annuity is not associated with your employer plan. You purchase this on your own using after-tax money.

Annuities come in different flavors. The main ones are “fixed” (DIA), “fixed index” (FIA), and “variable” (VA).

Deferred income annuity

Fixed-income annuities (in our case, “deferred income annuities”) will pay you a fixed payment for the rest of your life. Their overall return is slightly better than CD’s or Treasuries.

Once annuitization starts, you’ll receive a payout composed of part of your original premium plus interest. If you live longer than the insurance has estimated, you’ll probably get back your entire premium and the payouts will be interest-only.

Fixed index annuity

Fixed index annuities (FIA) are tied to an index, usually the S&P500. You start with a guaranteed minimum return that applies even in poor market years. During a good market year, you may enjoy a higher return (minus dividends).

Note, that the return on an FIA is not like being invested in the S&P500. Instead, its return is more like holding bonds. In exchange for the downside protection—that guaranteed minimum return—you give up some of the upsides.

Variable annuity

The third type of annuity is the variable annuity. In a VA, you invest your premium in various sub-accounts that resemble mutual funds. You may allocate your funds between stock and bond funds, moving it all around as you like, according to your risk tolerance.

However, keep in mind, with fees you will not get returns like those of the investments within your 401K.

Assuming you’ve also purchased a guaranteed lifetime withdrawal benefit (GLWB), in the long run, this may offset your lower returns. Maybe.

For both FIA and VA annuities, as the market hits new highs you get a permanent increase in your GLWB.

Needless to say, FIA and VA products are complex, with many variations. Comparing them to garden variety investments can be tricky. They don’t exactly advertise their returns, which are difficult to calculate.

But if you have extra savings to stash, they do provide a tax-advantaged haven for growth.

When the money comes out, however, part of it will be subject to taxes. In this case, you used after-tax dollars initially. When you receive a “return of principal” that money has already been taxed and won’t be taxed again.

However, money that you receive that has been earmarked as earnings will be taxed.

Annuity downsides

Most of the early withdrawal rules of IRAs also apply to annuities. If you take your money out prior to age 59½ you will be hit with an additional 10% penalty. The usual exceptions include death, disability, or equal periodic payments.

It is expected that you will keep your annuity for a minimum number of years, usual 6-8. If you bail out early you may be subject to surrender charges.

The good news is if you don’t like your annuity, after the surrender period, you are free to do a 1035 exchange for a different annuity. There are no tax consequences from this exchange

For example, once you retire you may prefer a fixed-income annuity to your current complex variable product.

Photo by Rudolf Kirchner from Pexels

5. Life Insurance

You may already have $50,000 worth of group term life insurance with your employer. Term insurance only covers you for a term, or in this case, during the “term” that you’re employed. Other term insurance is sold for fixed terms such as 5, 10, 20, and even 30 years.

In contrast, whole life insurance covers you for your “whole life”. A portion of your premium goes into a cash account that grows over time. For most whole life policies this cash account has a very small rate of return.

You may surrender the policy at any time for the cash value (minus any applicable surrender fees).

Like annuities, there is a vast array of more complex products available. With a Variable Universal Life (VUL) insurance policy, you can deposit your premiums (minus fees) into separate sub-accounts that resemble stock and bond mutual funds.

As with variable annuities, you may rebalance and move funds from one sub-account to another without any issues. But, like your other invested savings, there is no guaranteed return.

In addition, the Consumer Federation of America (CFA) warns that VUL policies are expensive. This 2003 CFA report found a VUL to perform better than a regular taxable index mutual fund plus term life insurance.

However, they cautioned that tax laws are likely to change during the decades that you’ll hold these products. Indeed, capital gains tax rates have dropped since 2003, so your invested savings outside a tax-advantaged account may do just as well, even with taxes.

Max out your 401K first.

As with annuities, you are placing after-tax funds into an account where those funds can grow free of taxes.

Cash value may be withdrawn, and any portion from earnings will be taxable.

Again, if you don’t like your life insurance policy you may make a 1035 exchange for a different policy. Likewise, you can exchange a life insurance policy for an annuity—but not vice versa (at least not without paying taxes).

Life Insurance loans

Some choose to withdraw cash in the form of a loan which is usually not taxable. However, there’s a risk that the loan plus owed interest will compound faster than the underlying cash balance, wiping it out and causing the policy to lapse.

If you are still living when a policy lapses, significant taxes could be owed.

Assuming your policy doesn’t lapse, once you die, the death benefit will be reduced by the cost of the loan plus interest owed.

Life Insurance death benefit

The best use of life insurance is to save most of it for your heirs (with an occasional loan for emergencies). Your death benefit most likely will go to your loved ones free of taxes.

(Note, for a very large death benefit, estate taxes may apply if you maintained ownership of the policy.)

Unless you added an optional rider to include the cash value, upon your death your heirs will get only the death benefit. Your cash value will go back to the insurance company. (Or stated another way, the insurance company will give the heirs the cash value, plus the difference between the death benefit and the cash value.)

If you are nearing the end with a hefty cash value call up your insurance agent and see if you can convert the cash value to a larger death benefit.

Photo by Noel Nichols on Unsplash

6. 529 college savings plan(s)

Are any of your close friends or family members planning to go to a trade school, college, or university? You can set up a 529 plan (also called a qualified tuition program or QTP) for each of them.

After-tax money goes in, grows tax-free, then comes out free of taxes if it’s used to pay for qualified educational expenses: tuition, fees, books, supplies, equipment, room and board (if at least half-time), plus a computer, computer software, and internet access.

With the recent TCJA tax changes, you can even pay up to $10,000 per year for tuition for K-12 education with a 529 plan.

Every single state has their own programs (or two or three). You do not need to live in the state to use their 529 program, nor does your college-bound beneficiary need to attend a school in that state. So, you have 50 plus choices!

Check your own state first as there may be state tax breaks.

The usual amount that you’ll probably contribute is the $15,000 annual gift tax exclusion. You are allowed to gift $15,000 to as many people as you like every year with no tax implications. In this case, you may use your gift for a 529 contribution.

If you have more cash on hand you can also contribute $75,000 which will count as your gift for this year and the next four years ($15,000 x 5 = $75,000).

If for some reason junior joins a rock band and doesn’t go to college, you can transfer the plan to another family member.

Likewise, you can always spend the money. However, any earnings not used for a Qualified Educational Expense will be hit by taxes, plus a 10% penalty. (But no penalty or taxes on the portion you originally contributed.)

7. Invest taxable money in tax-efficient funds

At the end of the day, you may be stuck with extra savings in your taxable brokerage account. This is not necessarily a bad thing. There are still ways to optimize your returns with regard to your owed taxes.

Conservative investing

If you are a conservative investor and in a high tax bracket, then municipal bonds may be for you. These bonds are free of federal taxes.

If your municipal bond is for a local project you may also be free of local and state taxes.

Keep in mind that “munis” pay less than other bonds, so you’ll need to do a bit of math.

- Perhaps you are considering a regular bond that pays 5%, vs a municipal bond paying 3%. You are in the 32% tax bracket. Which bond has a better return?

- After taxes, the 5% bond will have a return of 3.4% (5 x (1-.32))

- In this example, the regular bond beats the muni

Warning, the income from some types of municipal bonds are added back to your income when calculating the AMT. So much for their tax advantage!

These bonds are called private activity municipal bonds and provide funding for private projects (eg, airports, sports stadiums, etc.), as opposed to the usual public or government projects (like roads).

Moderate to aggressive investing

When held for over one year and sold, stock gains are taxed as capital gains.

Income from dividends, bond interest, and anything held less than one year is taxed as regular income and may be subject to the maximum tax of your current income tax bracket.

For any of us, our capital gains rate will be less than our regular income bracket, usually 15%.

You’ll want to keep your income-generating funds, including bond funds, within your tax-advantaged accounts. And load your brokerage fund up with stock.

(Not including the emergency fund kept in a money market fund.)

Look for “tax-efficient” funds. These will be stock funds, usually heavy on “growth”, with few dividend-producing stocks. If a fund has high “turnover” there will be more long- and short-term capital gains.

To determine the tax efficiency of your favorite fund, look under the “performance” tab in the research section of your brokerage account. Look for the return “before taxes” and compare it to the return “after taxes on distributions”. The latter will be a bit less but will give you an idea of what you may be losing to taxes.

Good luck!

Additional Reading

Stretch Your Retirement Savings with the Addition of an Annuity

Rollover Revisited: Why Sticking With a 401K May Be Better. Should you rollover your retirement savings to a new employer’s 401K or a rollover IRA?

Best Way to Save for Your Kid’s College? Contribute to a tax-advantaged 529 account

This information has been provided for educational purposes only and should not be considered financial advice. Any opinions expressed are my own and may not be appropriate in all cases. All efforts have been made to provide accurate information; however, mistakes happen, and laws change; information may not be accurate at the time you read this. Links are included for reference but should not be considered an implied endorsement of these organizations or their products. Please seek out a licensed professional for current advice specific to your situation.

Liz Baker, PhD

I’m an authority on investing, retirement, and taxes. I love research and applying it to real-world problems. Together, let’s find our paths to financial freedom.