2023 UPDATE

Contribution Limits for 2023

From IRS.gov

- IRA contribution of $6,500, with $1,000 catch-up

- 401K contribution of $22,500 with $7,500 catch-up

- SIMPLE contribution of $15,500 with $3,500 catch-up

TOTAL contribution for a defined contribution plan (like a 401K) of $66,000

- TOTAL includes contributions from employee, employer, and after-tax

- With catch-up contributions, the TOTAL becomes $73,5000

For more information see our TAX SAVINGS page

Should you roll over your retirement savings to a new employer’s 401K or a rollover IRA?

Congratulations, after working your way up the career ladder, you’ve landed your dream job at a great new company.

Hopefully, they will provide you with a shiny new defined contribution retirement savings plan, such as a 401K, 403(b), or 457(b).

However, this isn’t your first job (or perhaps, even your fifth job). You have one (or several) 401K account(s) from your old employer(s).

So, what do you do with that 401K savings when you change jobs?

You have three choices:

- Keep your 401K with the plan from your old job

- Roll the 401K money into an IRA

- If allowed, roll the 401K money from your old job’s 401K to your new job’s defined contribution retirement savings plan (reverse rollover)

In a previous post, I discussed the pros and cons of each of these approaches. However, there are some additional considerations that may tip the scales in favor of the 401K route.

Keep your retirement savings in a 401K

The biggest argument for keeping your savings in a 401K—either in your old job or your new—is ERISA protection. ERISA is the Employee Retirement Income Security Act (1974) which provides broad protection for many workplace retirement plans.

Namely, if someone were to sue you, or if a creditor were to come after you, they can’t touch your 401K

The only ones who can touch your 401K are your ex-spouse or the IRS.

An IRA, on the other hand, doesn’t share this security. You are protected up to 1.3 million dollars in case of bankruptcy, but otherwise, creditors and courts can take your money. (And obviously the ex and the IRS as well.)

If most of your retirement savings is tied up in IRAs, don’t fret; this is an ever-evolving legal area. Anecdotally, there have been cases where courts have also treated IRAs as untouchable.

There are other advantages to the 401K.

If you need a loan, 401K’s can accommodate you, but IRA’s cannot

Photo by Tobias Aeppli from Pexels

Roll your 401K savings into an IRA

The biggest argument for moving your savings into an IRA is choice and cost. Your 401K provides a limited choice of options: three funds minimum, or a dozen if you’re lucky.

Dig into the fine print and see what fees you are paying. If you are paying greater than a 1% expense ratio you are paying too much.

You can set up an IRA at any financial institution you like. Feel free to shop around and look at the choices available and the fees that are charged.

My three favorite financial institutions are Fidelity, Charles Schwab, and Vanguard. (I have accounts at all three, but I’m not affiliated.)

One of the three above offers index mutual funds for the low low price of…wait for it…0% expense ratio! (I’ll let you figure out which one…)

And if you don’t want an index fund, you can choose virtually any mutual fund or exchange-traded fund in existence. Or build a bond- or CD-ladder if that’s your thing. The choices are (almost) endless.

In addition, if you need money for your kid’s college you can tap an IRA

However, you can’t tap the 401K (unless you take it as a loan).

Facilitate Roth conversions by keeping funds in a 401K

However, another key advantage of the 401K is to sequester your “Traditional” money, allowing for smoother backdoor Roth IRA contributions.

A little background first. As you’re probably aware, both 401Ks and IRAs come in two flavors: Roth and Traditional.

“Traditionally” you get a tax deduction on the money you set aside, which then gets to grow tax-free. But unfortunately, it gets taxed when you take it out at your marginal tax rate at that time. (No special capital gains tax rate, unfortunately.)

Roth IRAs and Roth Accounts work the reverse of Traditional accounts: you pay taxes on the money going in, but no taxes when you take it out. Also, all those gains you’ve made over the years—or several decades—come out tax-free as well.

(Assuming you followed the IRS rules) you never pay taxes on those Roth earnings.

Roth vs Traditional. What if you don’t’ get the percentage “right”?

Roth or traditional? Where should you put your contributions? I go into greater, detail elsewhere, but here is the cliff notes version:

According to conventional wisdom, this decision should be based on how your current tax bracket compares to your (guesstimated) future retirement tax bracket.

If you’re just starting out at the bottom of the corporate ladder, you’d like to think your lifestyle will get better. And you have many decades for earnings to accumulate tax-free. Go Roth.

If you are older, making good money, and plan to downsize just a tad during retirement, then go Traditional.

Ideally, you should retire with both Traditional and Roth money. Deciding what percentage of each to cash out in any given year will allow you to pick your tax bracket.

(For more on picking your tax bracket, see my post HERE.)

If you’re planning a lavish lifestyle in retirement (eg, higher tax bracket), then the more Roth you have the better.

If you’re frugal and plan to continue that way during retirement (eg, lower tax bracket), then you can afford to save more via the Traditional route.

If you’ve been good at planning from day 1, you probably have mostly Roth, with perhaps some Traditional from your later (wealthier) working years.

Or perhaps, like me, you went mostly the traditional route to avoid taxes. And now you have too much Traditional, and not enough Roth.

The good news is that you can convert traditional IRA savings at any time. You simply need to pay the taxes.

Photo by James Wheeler from Pexels

Best time to convert to a Roth?

The best time to convert is when your taxes are low. New in your career and not making a lot? Do a conversion.

Taking a “mini-retirement” break? Do a conversion.

Recently retired, and living off taxable savings? Do a conversion.

Converting a little at a time

You can also do a conversion during one of the rollover job-changing scenarios above. However, if your 401K is relatively large, to keep taxes manageable, you’ll probably only wish to convert a smaller chunk of it in any given year.

If your 401K funds from your previous employer contain mostly Traditional money, and you’d like to start systematically converting it, then check if your new employer has in-plan conversion options (it might not).

If not, then you’ll need to keep your funds either in your old 401K or a Traditional rollover IRA. When you’re ready to convert, either take a partial rollover from the old 401K or convert a portion of your Traditional IRA. Either way, the converted funds will end up in your Roth IRA.

You may either keep your Roth IRA or roll some or all funds into your new employer’s 401K Roth Account.

(Note that not all defined contribution retirement savings plans support Roth accounts.)

Peak earning years

During your peak earning years (eg, your forties and fifties) you are being hit with taxes and may have little to no opportunity to convert.

At the same time, you *finally* can save a decent amount.

Ironically, at the same time, your income now limits your IRA contributions. If you make over $139,000 (single, 2020) or $206,000 (married filing jointly, MFJ) you can’t make a Roth contribution at all.

You can always make a Traditional IRA contribution, but you can’t deduct it if you have a retirement plan at work (that 401K) and your income is over $75,000 (single) or $124,000 (MFJ).

Backdoor Roth using after-tax contributions

The solution is the backdoor Roth contribution and mega-backdoor Roth contribution.

I discuss the basics here. To review, if you’re not eligible to make an annual Roth contribution, you’re always eligible to make a Traditional IRA contribution. However, depending on your (high) income, that contribution is most likely not deductible.

No worries make the contribution anyway. Step 1.

(However, contribute after-tax dollars to a separate IRA account. If you commingle this money with your other Traditional IRA money in the same account, that IRA money most likely can’t be reverse-rolled into your 401K plan if you choose to later.)

Step 2, whenever you like (it doesn’t need to be the same year), do a Roth conversion on that money and move it to your Roth IRA account.

Step 3. Pay taxes.

Wait, what?

Photo by Tobias Aeppli from Pexels

Taxes and the pro-rata rule

You already paid taxes on that after-tax money that you just converted. (Hence, the term “after-tax”)?

But you may have to pay taxes twice (temporarily).

When calculating your taxes on any conversion, the IRS requires that you treat *all* of your IRAs in aggregate. So, if you have multiple IRA accounts, the IRS treats them as if they are all one big fat account.

Perhaps you rolled over the large 401K account from your previous employer into an IRA. That counts.

In addition, perhaps that 401K account contained mostly Traditional money.

For example, let’s say you have $500,000 in traditional IRA money, and $12,000 in after-tax IRA money (two years of contributions). You do a conversion of $12,000.

From the perspective of the IRS, a portion of that $12,000 came from your traditional pile and a portion from the after-tax pile. So only 12/500 of that will be free of taxes, the rest will be taxed.

However, what if instead of rolling over your Traditional 401K money you kept it in a 401K, either the old one or the new one.

Now the only traditional IRA money you have are previous IRA contributions. These contributions may be a relatively small amount. You may have long since converted them or made them as Roth contributions to begin with.

In an ideal world, 100% of your IRAs contain Roth money. So then when you contribute after-tax money and Roth convert that money, no taxes are owed.

Which brings us to the next (long-winded) reason keeping your money in a 401K may be preferable to an IRA.

Using your 401K account to sequester your Traditional pre-tax contributions and earnings allows Backdoor Roth conversions to avoid taxes

Mega-backdoor Roth using after-tax contributions

Like the backdoor Roth with IRA contributions, you can do a similar thing with your 401K.

In 2019 you’re allowed to contribute up to $19,500 (or $26,000 if age 50 or older). Depending on your plan, some of that will be Traditional, and some may be Roth.

However, if you’ve maxed out your $19,500 you can add more, up to the limit of $57,000 (or $63,500 for the 50+ crowd). Note that any contributions your employer makes also count toward this limit.

Assuming your employer isn’t super-generous, and you’re allowed to go above the $19,500 limit, this additional money is called an “after-tax contribution”. (Not to be confused with a Roth contribution that is also contributed after taxes are paid, or after-tax.)

If your 401K plan allows in-plan conversions, you may convert this money to official Roth money.

Otherwise, you’ll need to wait until you change jobs and can roll the money out. While you wait, any earnings on this after-tax money will be treated like Traditional pre-tax money.

(This is different from Roth earnings, that are also after-tax, but are treated as Roth money.)

Image by Pixabay

Rollover 401K funds to finalize a Mega-backdoor Roth

Assume you can’t do anything with those after-tax dollars until you leave your current job.

Yes, you can leave your after-tax dollars in your old 401K. But recall that all the earnings, which are compounding, are considered Traditional. You need to move the after-tax money to a Roth in order for future earnings to also be considered Roth, and never be taxed.

- You could do a partial rollover; however, money comes out in a particular order during a direct rollover; pre-tax Traditional money first and after-tax money last. So, for this strategy, you’ll need to rollover the entire thing to move the after-tax money.

- You may have the option of sending part or all of the Traditional and Roth money directly to the new 401K. However, most 401Ks don’t take after-tax contributions from other plans.

- Alternatively, you may wish to roll your 401K money into IRAs first. This might be necessary if you wish to Roth convert some of your traditional money and your new 401K doesn’t support in-plan Roth conversions.

Your after-tax contribution may come back to you in the form of a check. You can always deposit that check in the bank if you like. . . But you should put it in your Roth IRA.

Traditional money and earnings on your after-tax contributions will go to your Traditional IRA. Roth money, Roth earnings, and the original after-tax contribution will go to your Roth IRA.

At this point, you can:

- Convert, some or all of the traditional IRA into Roth

- Hold some or all of the traditional IRA for future planned conversions

- For money you don’t plan to convert, if you haven’t already, reverse rollover it to your new employer’s 401K

- For the Roth money, either keep it in the Roth IRA, or reverse roll it over to your next employer’s 401K

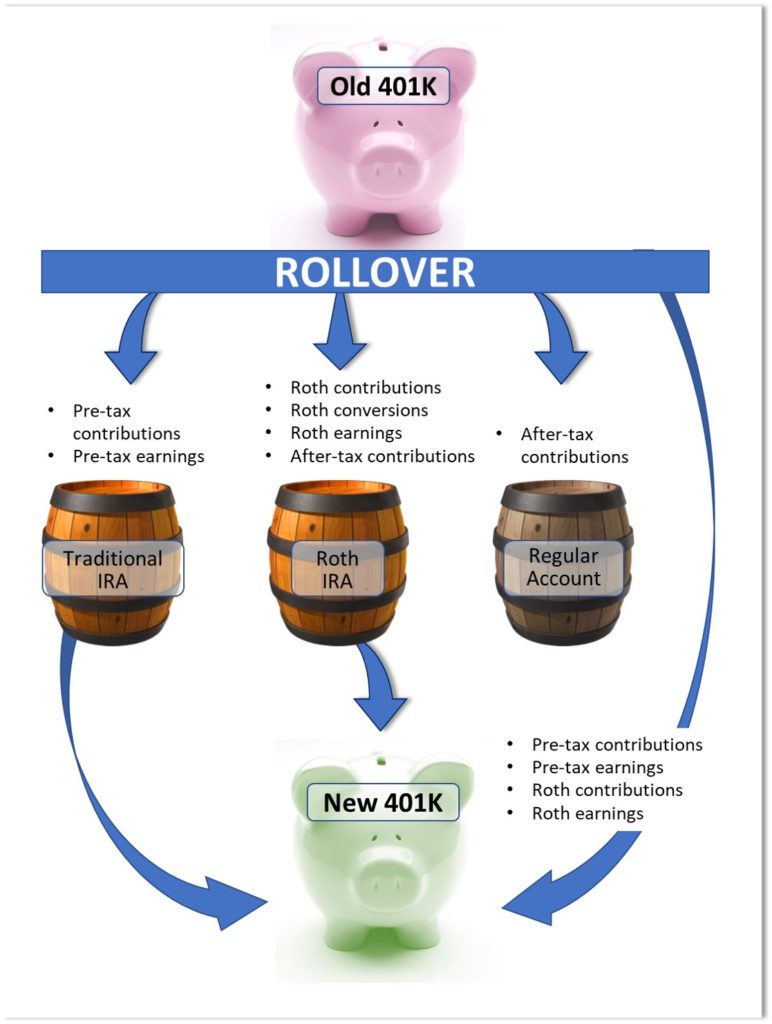

Funds from your old 401K may be rolled directly into a new 401K. (All except after-tax contributions.) Alternatively, some or all funds may be rolled over to a Traditional and Roth IRA. From there, funds can either stay or be rolled over into the new 401K. After-tax contributions can either go to a Roth IRA or simply into your bank account. (“Pre-tax” = traditional)

An emergency fund for your emergency fund

You may recall that you can take out Roth IRA contributions at any time, tax and penalty-free (they come out first). Obviously, you can’t put this money back. This is an emergency fund for your emergency fund. (You can’t do this with Roth accounts, as money comes out pro-rata.)

So, keeping some of your Roth money around in a Roth IRA may be beneficial. Roll the rest back to your new employer’s 401K. Worst case, you can take a loan from your 401K.

Direct vs Indirect rollover

There are two ways to rollover money from a 401K to an IRA (or other Plan): direct and indirect.

Indirect is not recommended. You get a very large check and you have sixty days to deposit it with the financial institution where you set up your new (or old) IRA. Taxes will be taken out, but you are responsible for placing the *entire* amount with your new IRA.

The only situation where you might do this is if you need to “borrow” that money for sixty days. Perhaps you’re buying a new home before you can sell the old one.

The preferred method is the direct method. Set up your IRA first (take note of your account number), then call the financial institution where your 401K resides and ask them to send the money directly to the other financial institution. (This is even easier if both accounts are at the same institution.) You never touch the money.

My ideal strategy

If I had the benefit of hindsight, this is the plan I would have followed. This may or may not align with your own situation.

IRA contributions

- Contribute annually to a Roth IRA

- When you are “too wealthy” to contribute to a Roth—and are paying real taxes—instead contribute after-tax dollars to a traditional IRA

- Convert the after-tax money to a Roth

401K contributions

- When you’re just starting out, contribute mostly to the Roth account

- As you get older, make more, and are facing real taxes, contribute a portion to a traditional account

- If you have extra money you can save, contribute after-tax dollars to your 401K (up to the limit)

Job changes

If you have significant after-tax dollars in your old 401K, get them into a Roth IRA ASAP:

- Rollover the entire 401K account

- Rollover after-tax dollars to your Roth IRA

- If you like, convert some Traditional money by rolling it into the Roth IRA account and paying taxes

- Move the remaining traditional money to your new employer’s 401K. This traditional money can come directly from your old 401K, or it can make a pit stop in a traditional rollover IRA.

- If your new 401K supports Roth accounts, move a portion of your Roth money to your new 401K. Leave a portion behind in your Roth IRA.

If you don’t have significant after-tax dollars in your 401K you can either rollover the entire thing as above, or take your time:

- If you don’t need to convert traditional money move most or all of it to your new employer’s 401K

- If you’d like to convert some, leave that portion in your old 401K

- When you’re ready to convert, roll a portion into a Roth IRA and pay the taxes

- Repeat

- All after-tax dollars, including any Roth money, will come out last. Send it all to the Roth IRA.

- If your Roth IRA is getting too big, roll some of it into your new employers 401K

If your new employer 401K supports in-plan rollovers and you anticipate contributing after-tax dollars (after the usual Roth/traditional dollars):

- In this case, rolling over all your traditional money into the new 401K may not be the best plan. The pro-rata rule still applies within 401K plans. Instead, keep the traditional money either in the old 401K or in a traditional IRA.

- Perhaps you had after-tax money in your old 401K. Then you would need to get everything out and your traditional money now sits in a traditional IRA.

- Now that your traditional money sits in an IRA, this will make Backdoor Roth conversions problematic from a tax perspective

- But the trade-off is that it’s assumed that you can covert more by contributing after-tax money in your new 401K moving forward

Outcome:

- All after-tax funds are rolled over to a Roth IRA. They may stay there or be rolled again into a Roth 401K account.

- Some of the traditional money may be converted to Roth

- All remaining traditional money ends up sequestered in the account with the least amount of past or future after-tax contributions. Either the old 401K, the new 401K, or a traditional IRA.

- Roth money may be split between a Roth IRA and a Roth Account at the new 401K

- You will have a Roth IRA plus perhaps a small traditional IRA to hold money temporarily before its either converted or moved.

These scenarios all assume that the investment choices and fees charged by your old and new 401K are reasonable. It also assumes your new 401K supports a Roth account. If your 401Ks are horrible, you’ll need to rethink your strategy; perhaps everything will need to go to rollover IRAs.

How does your ideal scenario compare to mine? Depending on where we are on our journey, we can make a few tweaks and get back on track.

Photo by rawpixel.com from Pexels

Ten job changes

A few years back the Bureau of Labor Statistics conducted a study of Baby Boomers and found that during our lifetime (or rather, before the age of 50) we have over eleven jobs on average. That’s a lot of jobs.

If we’re fortunate, most of those jobs will offer a 401K retirement savings plan (or similar).

If you consistently rollover your old 401K money into new 401K accounts, by your eleventh job you have a very large 401K stash. All protected by ERISA.

Moreover, if you happen to still be working at age 72, you aren’t required to take Required Minimum Distributions (RMDs) from your current 401K.

Note, that past 401K’s and Traditional IRAs are still subject to RMDs.

Roth IRAs are exempt from RMDs, but Roth accounts sitting around in old 401Ks are not.

So that big 401K containing contributions from your last eleven jobs is completely safe from RMDs.

In summary, unless fees and investment choices are unreasonable, try to keep most of your retirement savings in a 401K account so that it is protected by ERISA. Creditors and litigators can’t touch your life savings.

If you make after-tax contributions, either to an IRA or your 401K, then keeping most of your traditional, pre-tax money in a 401K will simplify the taxes on Roth conversions of that after-tax money.

Your Roth money can be split between a Roth IRA and the Roth account within your 401K. This allows you to enjoy the advantages of both IRAs and 401Ks. With your IRA, you may take out Roth contributions in case of emergency. With your 401K, in addition to ERISA protection, you may also have access to loans (in case of emergency).

Good luck!

Additional Reading

- Congratulations, You’re Retired! Which Money Should You Spend First?

- To Rollover or Not to Rollover. Pros and Cons of keeping your nest egg in a 401K vs rolling it over to an IRA.

- The Backdoor Roth and Mega-Backdoor Roth. How to grow EVEN MORE tax-advantaged money for retirement

- Roth vs Traditional. Picking where to stash your retirement money for the best tax-advantaged growth

First photo credit: Javier Allegue Barros on Unsplash

This information has been provided for educational purposes only and should not be considered financial advice. Any opinions expressed are my own and may not be appropriate in all cases. All efforts have been made to provide accurate information; however, mistakes happen, and laws change; information may not be accurate at the time you read this. Links are included for reference but should not be considered an implied endorsement of these organizations or their products. Please seek out a licensed professional for current advice specific to your situation.

Liz Baker, PhD

I’m an authority on investing, retirement, and taxes. I love research and applying it to real-world problems. Together, let’s find our paths to financial freedom.