Approved methods to make distributions from your retirement savings before age 59½

First off, I’m incredibly jealous. Most of us will be working long after the official retirement age of 67.

But let’s say you’ve been financially savvy from day 1 and lived well below your means. Or maybe you work for one of the few startups that has taken off. Either way, you’re financially free! Congratulations!

You’ve been good and maxed out your retirement savings accounts, so much so that you have very little saved in a taxable account.

What exactly are you going to live on from now until age 59½ when you’re allowed to take the money out without that pesky 10% penalty?

No worries, you have a few options. These options fall into three main areas:

- Withdraw from your most recent 401K—age 55 and over only

- Withdraw substantially equal periodic payments (SEPP) from an IRA or 401K

- Withdraw from a Roth IRA; if needed, create a Roth ladder

Over fifty-five? Withdraw money from your most recent 401K

There is a shortlist of allowed distributions (withdrawals) from a Qualified Retirement Plan, such as a 401K.

One is separation from service if the separation occurred during or after the year you turned 55. In other words, assuming the Plan allows it, as you leave your last job you may take money out of that 401K if you are 55 or over (or turn 55 later that year).

(It doesn’t matter whether you quit or were laid off, you “separated from service”.)

If you worked for this company for a while and have a big 401K stash, then all is well.

However, what if you haven’t worked for them for all that long? IRAs and 401Ks from former employers don’t count.

In a previous post, I recommended rolling old 401K money into your current 401K. Over ten or so jobs later you have amassed a huge 401K at your current employer.

This will give you the flexibility to take money out if you are not quite old enough.

Photo by Tadeu Gabriel Arcieri from Pexels

Taking substantially equal periodic payments (SEPP) from an IRA or 401K

Both IRAs and Qualified Retirement Plans—old and most recent—allow periodic payments. (These may also be referred to as Section 72(t) distributions.)

If you separate from service, regardless of your age, you can use this method with your most recent 401K. Employed or not, you can use this method with any of your old 401Ks or IRAs.

These payments continue for at least five years, or until age 59½ if later. In other words, if you start when you’re 58, you’ll need to continue for five years, until age 63. If you start at age 40, you’ll need to continue this until age 59½.

There are three methods for calculating periodic payments. You get to pick one.

- Required Minimum Distribution method

- Amortization method

- Annuitization method

A good 72(t) calculator will provide you a comparison of all three options.

All three are based on your life expectancy. The periodic payments are calculated as if you are going to receive them for the rest of your life, even though you’ll probably stop them in five years or so and take distributions as you like.

To determine your lifespan, you can pick a table.

- Uniform life table

- Single life expectancy table

- Joint life and last survivor expectancy table

The factor in the table is the number of years the government thinks you are going to live. Singletons use the Single life table. The Uniform life table assumes you have a spouse (or beneficiary) close in age; the joint life and last survivor table assume you have a spouse (or beneficiary) more than ten years younger.

Note that if you use the Joint table you must have a beneficiary for the account of the appropriate age. If you have no beneficiary, you must use the single life table.

Required Minimum Distribution method

Of the three, this one is by far the easiest to calculate.

This is the same math used for RMDs—those payments from your retirement accounts that you must start after age 72. However, in this case, it’s not a “minimum” but the actual amount you get.

- Account balance divided by the factor from the table

Let’s say you’re 48 and have an account balance of $3,000,000. (If you’re “retired” it better be big.) According to the single life expectancy table, you have 36 more years… $3,000,000 / 36 = $83,333 annual payment.

(Divide by twelve for a monthly payment, if preferred.)

Payments are recalculated annually. This is an important advantage over the other two methods that are fixed. Over time, your account balance should continue to grow, and therefore your payments should keep up with inflation. Our forty-year-old should stick with this method.

However, the RMD method generates the lowest payment. If inflation is not as much concern—perhaps you need only five years of fixed payments—then the other two methods may be preferred.

Photo by Aleksandr Neplokhov from Pexels

Fixed Amortization method

This method uses our favorite annuity equation and a “reasonable” interest rate. The IRS is flexible on this interest rate as long as it is no more than 120% of the federal mid-term rate. (The federal mid-term rate is 2.24% for August 2019.)

$3,000,000 amortized over 36 years at 2.24% interest results in an annual payment of $122,283.

If you want less, simply reduce the percentage or use the RMD method above.

Fixed Annuitization method

This method is very similar to the amortization method. Start with the account balance and divide it by an annuity factor. This annuity factor is the present value (PV) of a one-dollar payment, paid over your remaining lifespan, using the interest above (and the same formula).

For some reason, this method doesn’t use the life expectancy tables above, but a different one. The result is very similar to that of the amortization method above.

(←scroll→)

| Account size: $3 million, age 48 | Required Minimum Distributions | Fixed Amortization | Fixed Annuitization |

| Annual periodic payment | $83,333 | $122,283 | $121,750 |

| Annually recalculated? | yes | no | no |

Don’t forget, if these are traditional accounts, all payments are taxable.

When arranging all this with your IRA or 401K custodian—the financial institution where these accounts live—make sure they know these are substantially equal periodic payments, so that they report it correctly on your end-of-year tax forms.

If not, you’ll simply need to fill out another form to let the IRS know what you are up to.

Like any advanced strategy, it is best to consult with your financial planner or tax advisor before implementing.

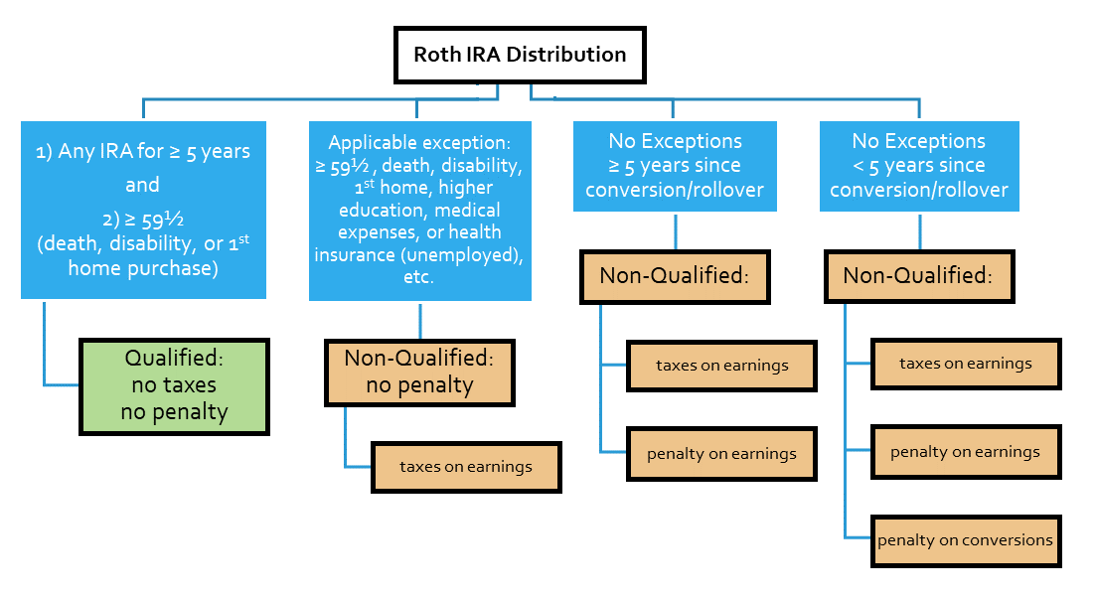

Roth contributed money, and Roth converted money after five years

Your Roth money is composed of three “types”.

• First the money you contributed, either to your Roth IRA, or in a Roth account in your 401K. (Or another employer-sponsored retirement plan that supports Roth accounts.) For an IRA, these are those ~$6000 annual contributions that you’ve made. For a 401K (or similar) it is a portion of the money removed from your paycheck.

• Second, traditional money that you converted to Roth. Again, this could be within your 401K, or when you rolled it over to a Roth IRA. This is money you’ve chosen to convert. You paid taxes on this money the year of the conversion.

• Third, any earnings on the Roth money above.

This is important to remember, because when you withdraw money from your Roth, it may come out in a particular order.

Photo by James Connolly on Unsplash

Money withdrawn (distributed) from a 401K, always comes out pro-rata, or by a percentage of the total. You get a little of this (pre-tax) and a little of that (after-tax).

However, money withdrawn from a Roth IRA always comes out in an order that corresponds to the list above: contributions first, conversions second, and earnings last.

You may recall that Roth contributions—the money that comes out first—may be taken out any time with no taxes and no penalties. (There are no taxes because you already paid the taxes before you contributed.)

If you have enough Roth IRA contribution money, you’re set.

If you don’t have enough, the second layer containing Roth conversions may make up the difference. There is one important caveat: the conversion must be five years in the past.

This is one of the “five-year rules” and it applies to each conversion separately. If you converted 50K five years ago you can take it out penalty and tax-free. If you converted another 50K only four years ago, you can’t touch that “layer” until next year.

And yes, if you have multiple conversions they come out in the right order, first-in-first-out (FIFO).

Note, if you have multiple Roth IRA accounts, it doesn’t matter which one you take your withdrawal from. The IRS treats all of them in aggregate.

In other words, if account A is the oldest, but you take a withdrawal from account B, that was only converted last year, it won’t matter, if the correct type of money resides somewhere in all your Roth IRA accounts.

Roth conversion ladder

You can be clever and create a Roth conversion ladder. Assuming you have enough money from other sources to support you for the next five years, convert just enough to support yourself in year 6.

Next year, convert just enough for year 7. Repeat.

You’ll end up with a “ladder” of Roth conversions that meet their five-year rule at the right time.

Because you’re converting only what you need, you are keeping taxes to a minimum.

Don’t forget about inflation

If $100,000 is enough for you this year, you’ll need more five years from now. Historically, inflation has ranged from 3-3.5%, however recently inflation has been low, around 2% or less.

Don’t forget to multiply your planned conversion amount by an inflation factor. You calculate this factor by determining how much one dollar would compound over the next five years.

I’ll do the math for you using 2% inflation: 1.104

If you need 100,000 to live on today, then you’ll need $110,400 five years from now.

(Yes, your 110K is growing in your account, but you can’t use the earnings without getting penalized. Save those for when you’re old enough.)

Age | The amount | The amount available |

48 | $110,400 | -NA- |

49 | $112,600 | -NA- |

50 | $114,900 | -NA- |

51 | $117,200 | -NA- |

52 | $119,500 | -NA- |

53 | $121,900 | $110,400 |

54 | $124,300 | $112,600 |

55 | -0- | $114,900 |

56 | -0- | $117,200 |

57 | -0- | $119,500 |

58 | -0- | $121,900 |

59 | -0- | $124,300 |

The amount converted at age 48 will be available five years later at age 53; the amount converted at age 49 will be available at age 54, and so on. Once you hit age 55 no more conversions are required. To calculate the next year, multiply the current year by 1.02 for inflation. All values rounded.

When the Roth money becomes available you can withdraw it without paying taxes. (However, you may be paying taxes for conversions for future years.)

You may wish to use a combination of a Roth ladder and equal periodic payments. Just make sure you have enough money—both Roth and traditional—when you hit age 59½ and for the decades beyond…

Photo by Sereja Ris on Unsplash

Another five-year rule. Keep enough in cash

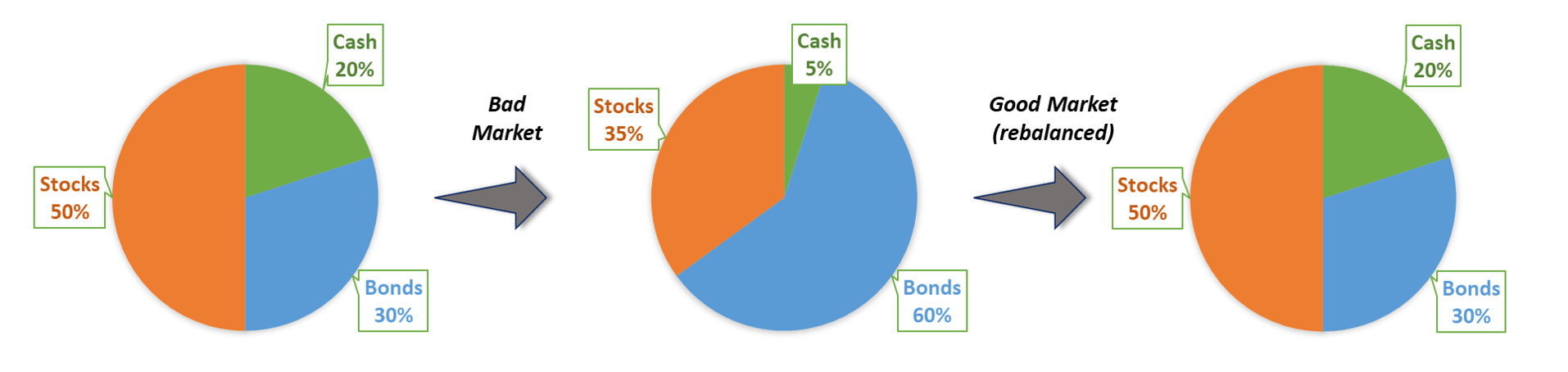

Another thing that all retirees—young and old—need to keep in mind is keeping enough cash on hand.

By “cash” I mean cash equivalents, such as a money market fund, CDs, or treasuries.

This is like your emergency fund. Except when you were working you probably only needed an emergency fund of 6-9 months to cover you if you lost your job.

The general rule of thumb is to keep what you need for the next five years in cash

What if the stock (or bond) market tanks tomorrow?

As you’re in it for the long-term you know all markets will recover. Eventually. But you don’t want to be cashing out any stock or bond funds after they’ve lost value. Instead, you’ll want to wait it out until the market recovers.

Historically, our worst bear markets last around two years, with additional years needed to get back to even. Our last market meltdown occurred in 2008. By 2013 it was back to its old highs.

Note, that if you have income unaffected by the market, you can subtract that from your five-year buffer. This income may include social security, a pension, an annuity, and/or a bond ladder. In other words, if you need 80K per year, but stable income covers half, then you only need five times 40K (plus inflation) in your “cash allocation”.

You can reduce your cash amount even further if you don’t mind losing a bit of discretionary income (money for the “fun stuff”) during poor market years.

If you have a higher risk tolerance feel free to reduce your cash allocation to say, three years.

If you are risk-averse, as long as you have enough growth from your remaining portfolio, you can increase your cash allocation to more than five years.

When markets are good, rebalance and sell stock or bond funds to keep your cash allocation full.

When markets are bad, you may rebalance the stock and bond funds relative to each other, but not the cash allocation. Draw down the cash allocation until either it’s depleted or the market recovers.

[flip your phone sideways for easier viewing]

A fictitious portfolio of stocks (or stock funds), bonds (or bond funds), and cash equivalents. In a bad market, the value of stocks goes down and the cash allocation is drawn down to pay for living expenses. Rebalance as usual by selling bonds (high) to buy stock (low). When the stock market recovers sell either stock or bonds to replenish cash.

For the IRA and 401K cash out strategies above, you can maintain five years of cash, just keep it in the IRA or 401K accounts that you plan to withdraw from. All accounts have an available money market fund—it’s usually the “default” fund.

And obviously, once you withdraw the money to use, keep that in a cash account, such as a money market fund in your taxable brokerage account or your checking account.

Good luck!

Additional Reading

How Much Money Do You Need to Retire Comfortably? How big is the stash, and how much do you need to save to get there?

- How Long Will You Live? (According to the Government). Or more importantly, how long does your savings need to last?

- Will You Run Out of Money? Closing in on retirement? How to manage your existing savings to last

First photo credit: Anton Avanzato from Pexels

This information has been provided for educational purposes only and should not be considered financial advice. Any opinions expressed are my own and may not be appropriate in all cases. All efforts have been made to provide accurate information; however, mistakes happen, and laws change; information may not be accurate at the time you read this. Links are included for reference but should not be considered an implied endorsement of these organizations or their products. Please seek out a licensed professional for current advice specific to your situation.

Liz Baker, PhD

I’m an authority on investing, retirement, and taxes. I love research and applying it to real-world problems. Together, let’s find our paths to financial freedom.