2023 UPDATE

Contribution Limits for 2023

From IRS.gov

- IRA contribution of $6,500, with $1,000 catch-up

- 401K contribution of $22,500 with $7,500 catch-up

- SIMPLE contribution of $15,500 with $3,500 catch-up

TOTAL contribution for a defined contribution plan (like a 401K) of $66,000

- TOTAL includes contributions from employee, employer, and after-tax

- With catch-up contributions, the TOTAL becomes $73,5000

For more information see our TAX SAVINGS page

Get started saving for your long-term financial goals

Congratulations, you’re out of school, working at a real job, and finally have a little extra to save. Where should you put these savings?

Some of this money should be held in an emergency fund, a savings or brokerage account where you can get to the money quickly. If the latter, invest in nothing riskier than a money market fund or a fund of US treasuries. This account should hold anywhere from three to nine months’ worth of living expenses.

Likewise, if you have a near-term goal, such as a down payment on a house, also treat this like your emergency fund.

But if you have extra money that can be left alone for a decade or longer, then the best thing to do is invest it. The easiest and most effective way to invest is through an Index fund.

Why invest in index funds?

As most of us don’t have the time, inclination, or risk-appetite to research and purchase individual stocks, we prefer to place our investment savings with a fund manager, usually at a mutual fund.

The fund manager takes on the responsibility of deciding what to buy and sell in order to maintain a diversified portfolio and earn an expected rate of return.

This fund manager may be actively choosing what to include in the fund, or they may simply be following the composition of an index.

However, historically, most active fund managers fail to beat the S&P500 index, even considering that some of them are “closet indexers”.

According to the S&P Dow Jones Indices SPIVA report for 2018, almost 65% of funds lagged the S&P500 in 2018! According to the same report, this issue has been seen consistently every year since 2001 and in all indexes analyzed.

If the S&P500 (or other indexes) beats the actively managed funds most of the time, then why not simply invest in the index?

Moreover, as the index fund manager isn’t doing much “work” simply matching the index, fees should be significantly lower than an actively managed fund.

Stock market indexes

S&P500

Before starting to invest in index funds, first it’s important to understand the indexes themselves, and what they do and do not include. Index funds contain all the stock of an index.

One of the most widely known indexes is the Standard & Poor’s 500 or S&P500®, which as the name suggests, contains the stock of 500 of the leading US-based companies. (But not necessarily the 500 largest companies.)

Companies must exceed a certain market capitalization (size) to be included. After meeting this and other criteria, a committee decides which companies are included.

The index is further weighted by the size of the included companies: bigger companies are represented more than smaller companies. At the moment, the top five companies represented are Microsoft, Apple, Amazon, Facebook, and Berkshire Hathaway.

Because the S&P500 is biased towards large companies, of all the indexes, it matches closest to the general behavior of the broader market. In other words, when this index is up, the entire market tends to be up.

DOW

The index reported most often in the news is the Dow Jones Industrial Average. This index is the oldest and has been around since 1896. However, it only contains 30 price-weighted companies, so its behavior may not necessarily match that of the broader market.

The thirty companies are blue-chips: large, well-established, dividend-paying companies which include (at present) American Express, Chevron, McDonalds, and Walt Disney.

Nasdaq

Most stocks in the US are traded on one of two exchanges, either the New York Stock Exchange or the Nasdaq. The Nasdaq trades mostly technology stocks, including the big ones: Apple, Microsoft, and Amazon.

The Nasdaq Composite Index includes almost all the stocks that trade on this index. The Nasdaq 100 Index includes the 100 largest nonfinancial Nasdaq stocks.

As many stocks in the S&P500 trade on the Nasdaq, there is overlap between the two indexes. However, technology companies tend to be growth-oriented and so the Nasdaq is more volatile (risky) than the S&P500. In other words, in any given day it tends to go up (or down) more than the S&P500.

Also, because the Nasdaq is biased towards technology stocks, it’s not as diversified as the other indexes. If a big company, such as Alphabet (Google) has a bad day, it can pull down the rest of the technology sector, along with the Nasdaq. Likewise, if another sector, such as financials, is doing well, that may not be seen in the Nasdaq.

Russell 2000

Both the S&P500 and Dow include large companies. But what about small and medium-sized companies? These are included in the Russell 2000.

The Russell 2000 represents the smallest 2000 companies of the Russell 3000. The Russell 3000 covers 3000 companies, representing 98% of the US stock market. Therefore, the Russell 2000 is the smaller two-thirds of the market (while excluding the tiny companies).

Like the S&P500 it is market-cap weighted so “bigger” companies within the index have more push than smaller companies.

Companies represented by the Russell 2000 tend to be growth companies, therefore the Russell 2000 is more volatile than the S&P500.

Note that sometimes the market will favor small growth companies and the Russell 2000 will be up more than the S&P500. Other times, the market will favor larger companies, and the S&P500 will be up, relative to the Russell.

Photo by Robert Stokoe from Pexels

International and Global indexes

Stock markets aren’t restricted to the US. There are exchanges throughout the world that buy and sell the stock of international companies. Depending on the region, and the exchange rate, these markets may be doing better (or worse) than the US market.

However, today more so than ever, all our economies have become interdependent, and therefore all markets, including the US, tend to react in tandem to global events.

MSCI and FTSE have several international and global indexes. “Global” indexes include US companies, while “International” indexes focus exclusively outside the US. To complicate matters, some of these indexes include only developed countries, while some include both developed and developing (emerging) countries. All combinations are available.

| Index | Includes US | Includes Developed countries (EU, etc.) | Includes Developing (emerging) countries |

| MSCI ACWI | |||

| FTSE All-World | |||

| MSCI World | |||

| MSCI EAFE | |||

| FTSE All-World ex US | |||

| MSCI Emerging Markets | |||

| FTSE Emerging Markets |

MSCI’s flagship global index is the MSCI ACWI (All Country World Index), which includes stocks from 49 developed and developing countries, including the US. Seventy percent of the index represents large-cap companies, with mid- and small-cap filling in the difference. Over half represents the US.

FTSE, the creators of the Russell Indexes, has their own FTSE All-World index covering large and mid-cap stocks from developed and emerging markets, including the US. Like the MSCI AWI, this index includes 49 countries, with over half its weight in the US.

Other variations include the MSCI World, which excludes developing countries but includes developed nations, including the US.

Countries represented in the MSCI World index include Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Hong Kong, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Japan, Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Portugal, Singapore, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, the UK, and the US.

In contrast, MSCI EAFE (Europe, Australasia, and the Far East), excludes the US and Canada but includes all other developed nations listed above.

Likewise, FTSE All-World ex US, includes the “All World” list, including both developed and developing countries, minus the US.

Emerging Market indexes

MSCI Emerging Markets, tracks only stock of companies within developing countries, including Argentina, Brazil, Chile, China, Colombia, Czech Republic, Egypt, Greece, Hungary, India, Indonesia, Korea, Malaysia, Mexico, Pakistan, Peru, Philippines, Poland, Qatar, Russia, Saudi Arabia, South Africa, Taiwan, Thailand, Turkey and the United Arab Emirates.

The Emerging Market Index is more volatile than any of the other indexes. These countries are growing their economies but have added political and economic risk.

Stock index mutual funds and ETFs

Mutual funds vs ETFs

Now that you’re ready to invest, you have a choice between a mutual fund or an Exchange-traded fund (ETF). A mutual fund is a large fund overseen by a fund manager, where many participants invest in the larger fund.

An ETF is like a mutual fund but has characteristics like a stock. For example, ETFs can be bought and sold during market hours, while mutual funds are only purchased after the market has closed.

From an investor standpoint, it doesn’t matter which you invest in. The key is the fees that are charged.

As these are index funds, performance should match closely to the underlying index, regardless of what vehicle you use to purchase the index. For example, except for fees, an iShares ETF will have the same performance as an Index mutual fund from Charles Schwab.

Index funds require very little “work” on the part of the fund manager as they are simply matching an index, therefore fees should be very low.

As ETFs are bought and sold like stocks, commissions may apply. Commissions used to run around $4.99 per trade, but at several institutions, are now completely free.

For mutual funds, ideally, there should be no “transaction fees”, such as a “load”.

For both mutual funds and ETFs, management fees are expressed as an expense ratio, or the percentage of your account you’ll be charged. Note, this percentage is charged regardless of whether your investment makes any money.

Your favorite financial institution

The next criteria is the financial institution where your money is invested. The best deal will be the funds provided by your financial institution. For example, if your money is with Fidelity, you have access to the “zero cost” index funds, provided by Fidelity.

Likewise, you get the best deal on Vanguard funds if your account is at Vanguard.

For many index funds, and almost all ETFs, it doesn’t matter where your account is located. However, first, compare prices at the financial institution where your money currently resides.

Total market and extended market funds

In addition to the indexes listed above, you also have the choice of investing in the entire US stock market through “total market” funds. These funds tend to behave like S&P500 index funds.

These shouldn’t be confused with “extended market” funds which contain small- and medium-cap funds like the Russell 2000.

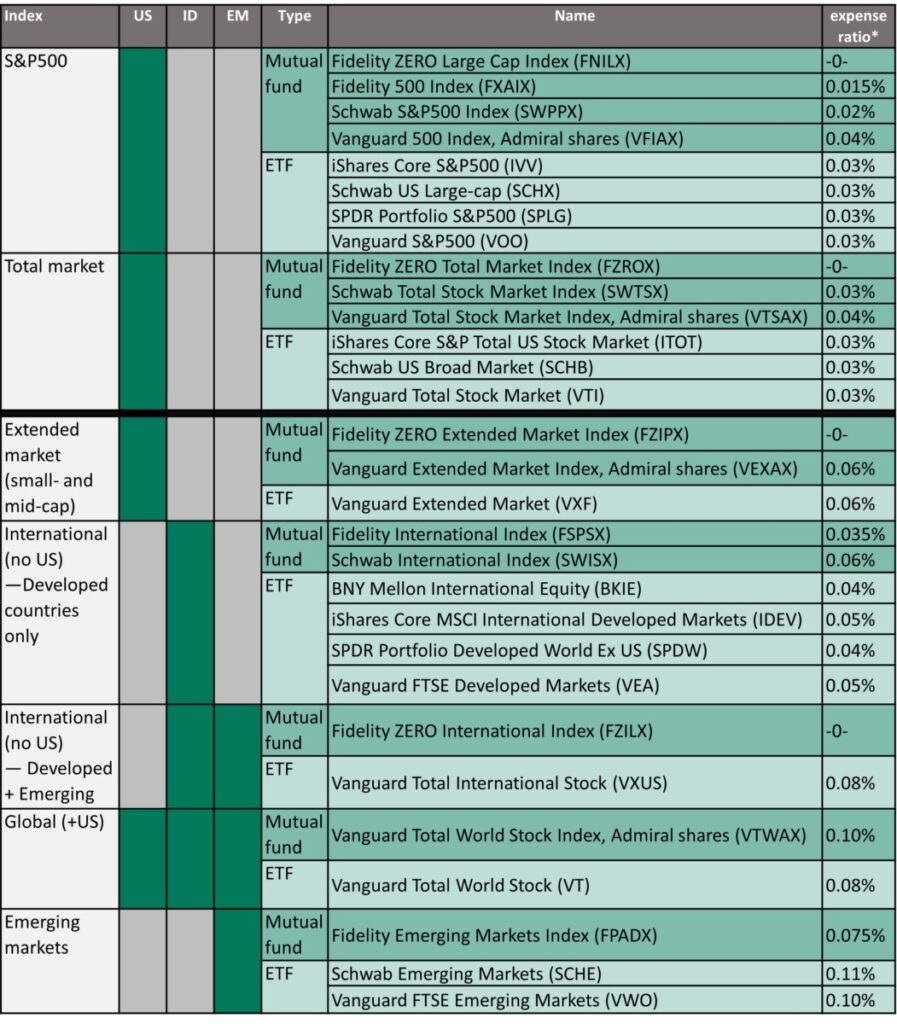

Below is a list of ideas, which is by no means exhaustive. The focus is on index funds with the lowest reported fees (< 0.10%). Note that many companies provide low-cost index ETFs, but the lowest cost index mutual funds (at present) tend to be with Charles Schwab, Fidelity, or Vanguard. (Disclaimer: I am NOT affiliated with any of them.)

Stock index investments

July 2021. US = United States; ID = International, developed countries; EM = Emerging markets. Funds are suggestions only; please do your own research before investing.

*Fees may change at any time and vary based on where the fund is purchased.

Building your stock portfolio—Basic version

Overwhelmed by this long list? Don’t be, simply pick a single item from the first section, representing either the S&P500 or a Total Market index.

Boom, you’re done!

You now have a fully diversified stock portfolio representing 500+ different stocks.

Building your stock portfolio—Intermediate version

You don’t have to, but if you’d like, you may add to the diversity of your stock portfolio. Add either the “extended” market index of small- and medium- cap stocks, and/or an International index.

Your S&P500 fund is the “core” representing 50-100% of your stock investment. Invest anywhere from 5-20% in one or more of the other types. There is no “correct” percentage, but the core should be the highest.

For example: 60% S&P500, 30% extended, and 10% international.

Keep in mind that “global” funds are half US. So, 20% Global equals 10% international plus 10% S&P500.

You may also add a small allocation of emerging markets but note the fees above are slightly higher. You may have enough coverage by simply investing in an international fund that includes emerging markets.

Once you start investigating on your own you may find even more index choices.

However, beware of “2X” and “3X” type index ETFs. These are special ETFs designed to produce “2X” the profit. However, they also generate 2X the risk, so avoid for now.

What about bonds?

So far, the discussion has centered around stock indexes exclusively. If your invested savings is for a goal fifteen-plus years out (eg, retirement) most, if not all, should be invested in stock.

However, you may have shorter financial goals (eg, Junior’s college fund) or simply be more risk-averse.

In the past bonds have sometimes made more than stock, but due to our low interest-rate environment of the last decade, bond yields have been very low. This, of course, could change at any time in the future.

Regardless, you may wish to leave a portion of your total savings in bonds, anywhere from 10-50% of the total.

Bonds are debt instruments that are either issued by companies (“corporate bonds”) or governments (“US Treasuries”).

US Treasuries

As the US has always paid its debts, US Treasuries are considered very low risk, and therefore pay very little. Indeed, many money market funds are filled with US debt.

Treasuries have different maturity dates:

- Treasury bills (T-bills) mature in less than one year

- Treasury notes (T-notes) are issued with maturities of 2, 3, 5, 7, and 10 years

- Treasury bonds (T-bonds) mature in 30 years

Most of the time long-term debt pays more than short-term debt. As interest rates are expected to change, either up or down, you are taking on a bigger risk with the long-term debt.

However, there are times when “the yield curve inverts” and this is no longer the case. The yield may be similar across all maturities, as short-term debt starts to pay more.

Corporate bonds

Corporate bonds are rated based on their risk of default, from AAA, the highest-rated, all the way down to C. “Junk bonds” are those at the low end.

Like Treasuries, corporate bonds also come in different maturity dates:

- Short-term: less than 5 years

- Intermediate-term: 5-10 years

- Long-term: greater than 10 years

Just as with stock, the more risk you take on, the better the potential payout. Junk bonds pay the best, followed by higher-rated corporate bonds, followed by Treasuries.

Bloomberg Barclays Bond Indexes

Just like stocks, bonds have their own indexes. One used often is the Bloomberg Barclays US Aggregate Bond index which contains both treasuries and corporate bonds. Bonds are of short- intermediate- and long-term maturity, with no junk bonds.

The Bloomberg Barclays US Corporate Index, follows only corporate bonds with at least one year until maturity.

Bond index mutual funds and ETFs

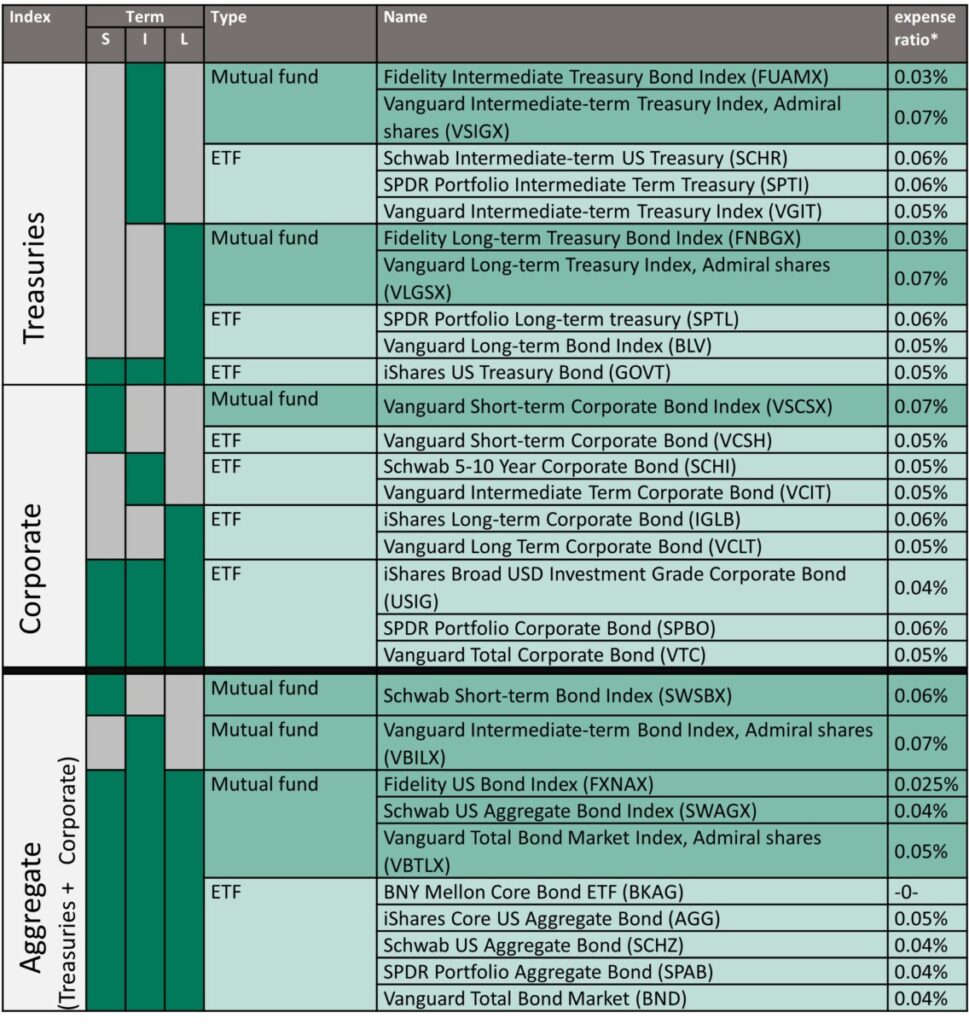

As bonds pay less (at present) it is important to keep expenses to the bare minimum.

If you wish to have a percentage invested in short-term US treasuries first look at the default money market fund provided by your financial institution. This is the equivalent of “cash” but does pay interest.

The funds listed below should pay out a bit more than “cash”.

Listed are 2-3 mutual funds or ETFs in each category with the lowest reported expense ratio.

July 2021. Funds of short-term only treasury bonds are excluded, as the default “money market fund” should be equivalent. Funds are suggestions only; please do your own research before investing.

*Fees may change at any time and vary based on where the fund is purchased

Adding bonds to your portfolio—Basic version

If you’ve decided that you would like to invest a percentage of your total portfolio in bonds (eg, 70% stock, 30% bonds), then the easiest is to simply add an “aggregate” index fund that contains both government and corporate bonds.

Pick any one item from the last seven lines of the table above. You’re done!

What is the “correct” percentage of bonds? There is no correct answer. Your portfolio should be “aggressive” enough to meet your financial goals, while still respecting your risk tolerance.

In other words, you’ll need a high percentage of stock to earn enough but may need some percentage of bonds to keep you from panicking during one of the many—temporary—market selloffs that will occur over the next many decades.

Adding bonds to your portfolio—Intermediate version

Just as you did with your stock allocation, you may also split up the bond allocation.

Perhaps split it between intermediate-term and long-term. Or split it between corporate bonds and government bonds. Any combination is allowed.

Just be aware that many of the funds listed above overlap.

Photo by Joshua Rawson-Harris on Unsplash

Fill up tax-advantaged accounts first

Employer retirement plans (eg, 401K)

While this money grows over the decades, the last thing you wish to do is pay taxes on it. Fill up your tax-advantaged accounts first.

If your employer offers a 401K (or SIMPLE, or TSP, or 403b, etc.), fill that up first.

In 2020 you may contribute up to $19,500 of earned income, into a 401K plan. If you are age 50 or over, you may contribute up to $6500 more, or $26,000 total.

If your employer provides a “match” of funds, do whatever you can to contribute the minimum. This is free money!

For example, perhaps your employer matches the first 3% of your salary that you contribute. You make $100,000 and contribute the maximum of $19,500. Three percent of your salary is $3000, which is matched by your employer. You now have $22,500.

If you can’t afford to contribute the max of $19,500, at minimum, contribute $3,000 to get the $3,000 match, for a total of $6,000.

In addition (or alternatively) your employer may simply contribute a fixed amount regardless of how much you contribute. Either way, it’s free money.

Your employer’s plan will have a very short list of investment choices. At a minimum, most plans offer at least one index fund, usually the S&P500.

Individual Retirement Arrangement (IRA)

In addition to your employer’s 401K, you may also contribute to an Individual Retirement Arrangement or IRA. For 2019 and 2020 the limit is $6000 maximum, plus an additional $1000 for those age 50 and above.

Note, that if your income is above a certain threshold you may not be able to contribute to a Roth IRA (see below).

Also, a higher income may disqualify you from taking a tax deduction on your traditional IRA if you participate in a workplace plan, such as a 401K.

Your IRA can be set up at any financial institution you wish, that supports IRAs. Also, keep in mind if you set up an IRA at one institution, you can always change your mind and “roll-it-over” to a different financial institution. There is no need to keep separate IRAs in separate places.

(There are always exceptions. Inherited IRAs must be kept in a separate account. Likewise, IRAs containing 401K money rolled over from a previous employer shouldn’t be “comingled” with the IRA money you contribute annually.)

Don’t forget to check-in

Index fund investing has the advantage that you can “set it and forget it.” However, you shouldn’t forget it completely. At least once a year look and see how your investments are doing.

If we are experiencing a market slump, don’t worry, those are temporary. Over decades, the market always goes up.

Are your financial goals still the same? Is your original allocation of stock to bonds still aligned to your goals and risk tolerance?

Do you need to rebalance? If the market has been good, your stock allocation will be “too high”; likewise, if the market is in a slump your bonds allocation may be “too high”. Sell the high percentage one and buy the low percentage one to get back to your preferred allocation. Some financial institutions will do this automatically for you.

Here is your checklist:

- Choose a financial institution for your IRA, and other savings

- Familiarize yourself with the funds available in your 401K or other retirement plan

- Bucket your financial savings goals by timeframe: college savings, retirement, etc.

- Decide on the stock: bond (or cash) allocation for each “bucket”

- Choose stock index funds (or bond index funds) available at your financial institution

- Reevaluate at least annually

Good luck

Additional Reading

- To Rollover or Not to Rollover. Pros and Cons of keeping your nest egg in a 401K vs rolling it over to an IRA

- Buy and Hold? Or Active Management. Navigating your life savings through stormy markets

- Roth vs Traditional. Picking where to stash your retirement money for the best tax-advantaged growth

This information has been provided for educational purposes only and should not be considered financial advice. Any opinions expressed are my own and may not be appropriate in all cases. All efforts have been made to provide accurate information; however, mistakes happen, and laws change; information may not be accurate at the time you read this. Links are included for reference but should not be considered an implied endorsement of these organizations or their products. Please seek out a licensed professional for current advice specific to your situation.

Liz Baker, PhD

I’m an authority on investing, retirement, and taxes. I love research and applying it to real-world problems. Together, let’s find our paths to financial freedom.